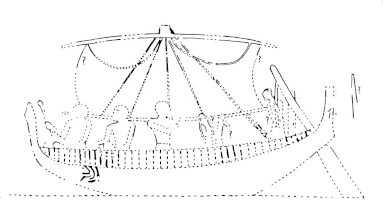

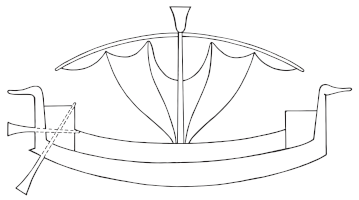

Only the rigging elements of the ship survive: the mast, a down-curving yard with a furled sail, a double backstay, and a top-mounted crow's nest. The central bunch of the sail is larger than those on either side. Coming down between each bunch are the brails. Parts of a second, identical ship are visible to the left, preserving only the right side of the crow's nest, the right end of the yard, the double backstay, and parts of the central large bunch of sail.

Merchant Syro-Canaanite ship

L3

Late 18th-early 19th Dynasty (late 14th- first quarter of 13th century B.C.)

Saqqara Memphite necropolis, unprovenanced block from a New Kingdom tomb

56 x 43 x 4.5 cm

limestone relief fragment from the upper portion of a scene, broken in the middle. The upper limits of the register are framed by a band of water.

Berlin ÄM 24025

Capart 1931: pl. 67; Emanuel 2014: 31-32, fig. 5a, 5b; 2015: 168, fig. 4; Knapp 2019: 129; Millet 1991: 89-91; Schulman 1968: 31, 33, fig. 5; Vinson 1993: 134, 136-39, figs. 4a-b (detailed analysis)

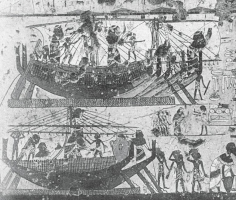

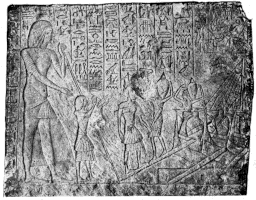

Five men are engaged in landing and unloading a ship with a brailed sail. The setting seems to be on the Nile based on the Nilotic fish and vegetation observable in the upper register. Vinson hypothesizes that this could be the Prw-Nfr dockyard at Memphis. In the upper left section, a man is shown crawling along the yard arm in an effort to bunch up the sail or to secure it in place. His left leg is visible despite the fact that the pendent lines are not ropes but the sail. That this was simply a mistake by the artist in confirmed by parallels from the Turin papyri 2031 and 2033. On the right, another sailor is crawling up a double backstay which possibly also served as a halyard for the yardarm. Three more crewmembers are unloading cargo on deck: the first and third seem to be carrying Canaanite amphoras, while the figure in the center is holding a basket. Below the left arm of the second amphora carrier in the lower right corner are what seem to be the mouths of two pithoi. Various additional objects are part of the scene, including a basket, a pilgrim flask (?), the mouth and shoulder of a jar, an elephant tusk (?) and some difficult to interpret hatch-marks. The basket and the supposed pilgrim flask are paralleled in one of the ships from Medinet Habu (far left middle row ship) which has a container suspended on the rigging. Parts of a second ship are visible on the relief on the left, including the right side of the crow's nest, the right end of the yard, the backstay, and parts of the central large bunch of sail. These elements indicate that the two ships were identical.

Vinson thinks there are signs that the composition was recut or modified over its lifetime, as indicated for instance by his interpretation of the basket carrying crewman as having two right hands - one across his chest and one held high (Vinson 1993: 137, n. 14). Although this is unlikely, the bottom left corner of the relief shows abbrasion in the form of diagonal lines of chisel marks, while patches of darker material observable in some areas of the relief are likely discolored plaster. According to Peter Brand, this was the result of incomplete smoothing of the stone block from the quarry, which was then finished by coating the surface with plaster either before or after the relief was carved - a common expedient in the latter parts of the New Kingdom period (Brand 2023, personal communication). It is quite possible that the relief was recycled in a later building project, which was a common fate of Amarna period blocks.

The rigging of this relief is remarkably similar to that of the ships from Medinet Habu. It is notable that the crow's nest only occurs in Egyptian art when depicting foreign, seagoing vessels. One difference observable compared to the Kenamun and Iniwia ships is that the crow's nest sits on top rather than being hung from the masthead. The Saqqara relief provides the earliest evidence for the development of the loose-footed sail and the top mounted crow's nest, and further strengthens the hypothesis that both were Levantine inventions.

Capart's initial dating based on the dress of the figures and the shape of the amphoras has been accepted by subsequent studies. The elongated head of the sailor climbing the backstay further strengthens this interpretation as it is very close to the Amarna-period style. Vinson argues that none of the elements require a date much later than Ramses II, with a terminus post quem of the early years of Tutankhamun and a terminus ante quem of the early 19th Dynasty. The closest parallels to the unusually squat Canaanite amphoras are KW 588 from the Uluburun wreck and amphora 282 from Akko grave C1, both datable to the immediate post-Amarna period and thus confirming the stylistic dating of the relief (Vinson 1993: 138). Peter Brand leans more to a late 18th Dynasty date (Brand 2023, personal communication).

Capart, J. 1931. Documents Pour Servir à L’étude De L'art Égyptien. Paris: Les Éditions du Pégase.

Emanuel, J.P. 2014. “Sea Peoples, Egypt, and the Aegean: Transference of Maritime Technology in the Late Bronze Age-Early Iron Transition (LH IIIB-C),” Aegean Studies 1.1: 21-56.

―――. 2015. “Sailing from Periphery to Core in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean,” in J. Mynářová, P. Onderka and P. Pavúk (eds.) There and Back Again – The Crossroads II: Relations between Egypt, the Aegean, the Levant, and the Sudan in the 2nd and 1st Millennia B.C.E. Prague: Charles University Faculty of Arts, pp. 163–180.

Knapp, A. B. 2018. Seafaring and Seafarers in the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Millet, N. B. 1991. "The First Appearance of the Loose-Footed Squaresail Rig in the Mediterranean," JSSEA 17.3: 89-91.

Schulman, A. R. 1968. “A Private Triumph in Brooklyn, Hildesheim and Berlin,” JARCE 7: 27-35.

Vinson, S. 1993. “The Earliest Representations of Brailed Sails,” JARCE 30: 133-150.