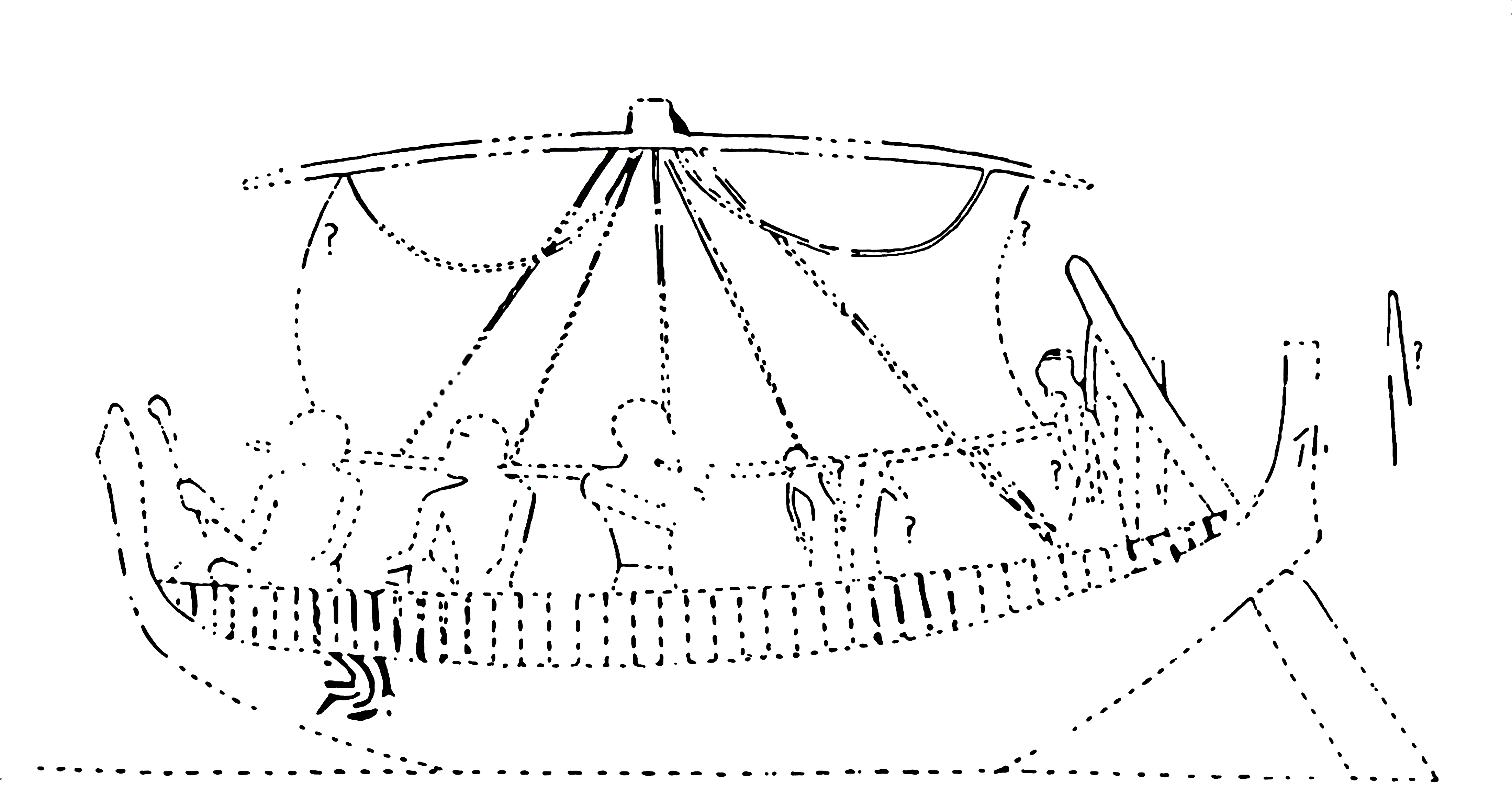

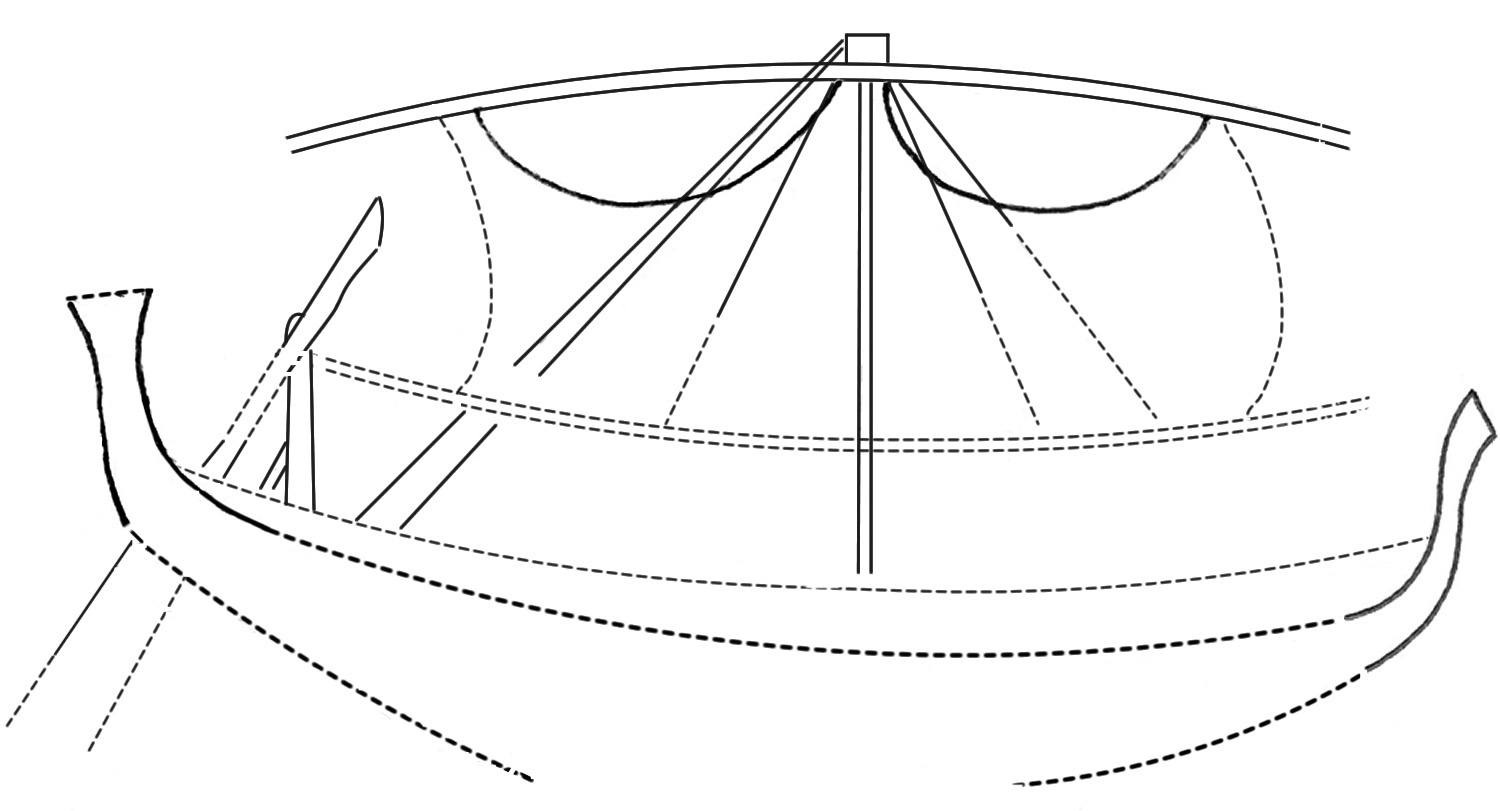

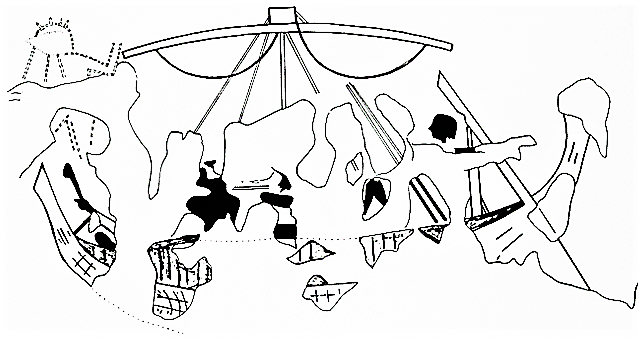

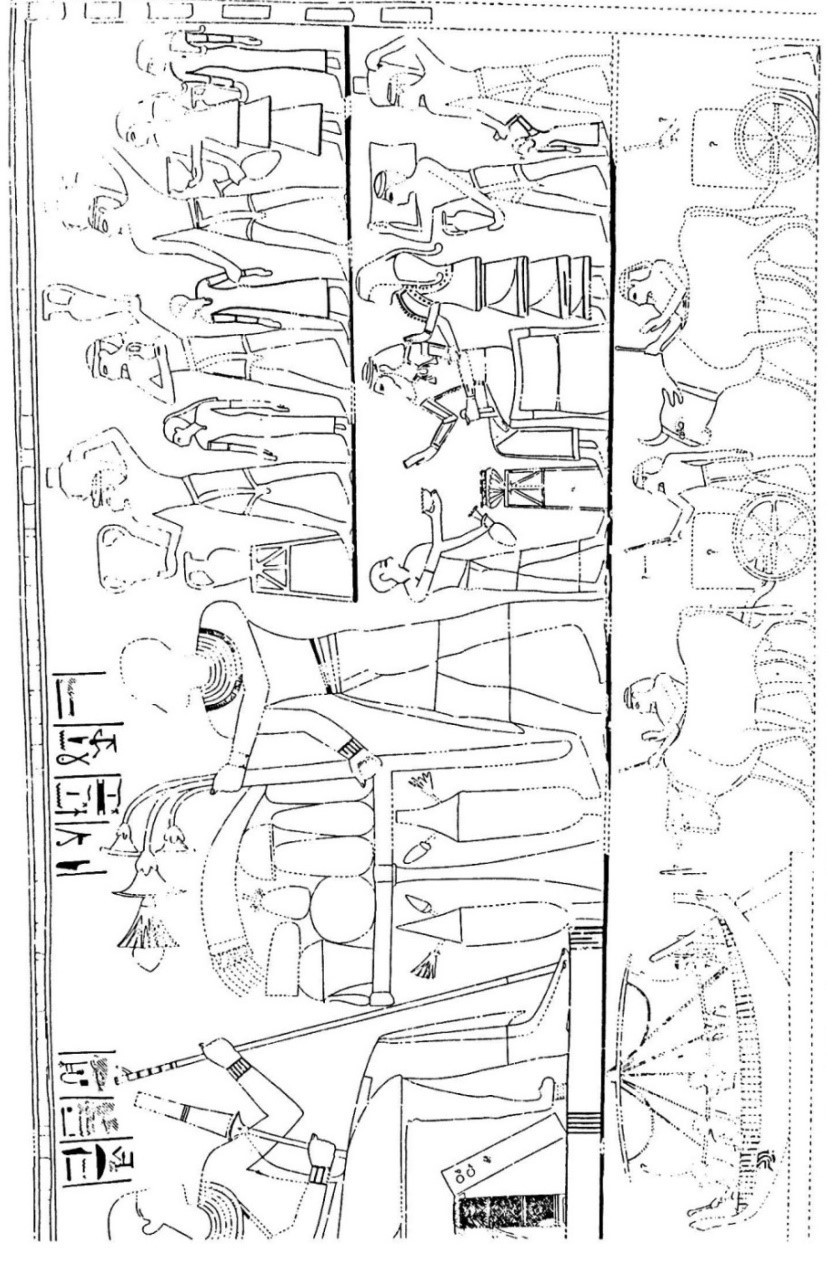

There are two published drawings which differ in the number of details they provide. The ship faces left, with a crescentic hull that curves smoothly upward into high vertical posts with undecorated extremities. The two posts are more or less identical, although the left-hand post is marginally shorter and has a gentler upward curve resulting in a small outward incline. The placing of the quarter rudder on the other side would indicate that this is the stempost, however in the later mnš determinative (L5) the quarter rudders are on the opposite side, which is the preferable reading. It is possible that the Kenamun artist has mistakenly flipped the rudder’s position. Müller’s drawing shows the hull and other wooden parts coloured in yellow, with two horizontal parallel lines running along the hull that likely represent planking seams, which are in turn intersected by a row of curved vertical lines. The latter are absent from Säve-Söderbergh's rendition, although he notes that there are orange lines over the yellow hull that possibly indicate the grain of the strakes. Above the sheer running the length of the ship is a screen painted red-orange filled by a row of vertical lines. A single quarter rudder is supported by a stanchion, an element that is absent in the later Kenamun ships. There is a tiller attached above the stanchion, which makes it identical to the Egyptian New Kingdom type of quarter rudder. There is a narrow mast amidships, with a yard with down curving tips raised to the top. The square object located at the masthead could be either the mast cap or a crow’s nest. The part of the painting where the boom would have been represented is no longer preserved; it is reconstructed in Säve-Söderbergh's drawing. Three diagonal lifts (one aft and two forward) support the boom, while the two lines aft are likely halyards. The two pendant arcs seen attached to the yard on either side represent a single lift. Wachsmann notes that in Müller’s drawing, the port lift is attached at a lower point on the mast, below its junction with the yard, while the starboard lifts cross across the yard and are connected to the square device at the masthead.

Merchant Syro-Canaanite ship

L1

c. 1430-1420 B.C. (Beginning of Amenhotep II's reign or slightly earlier, early 18th Dynasty)

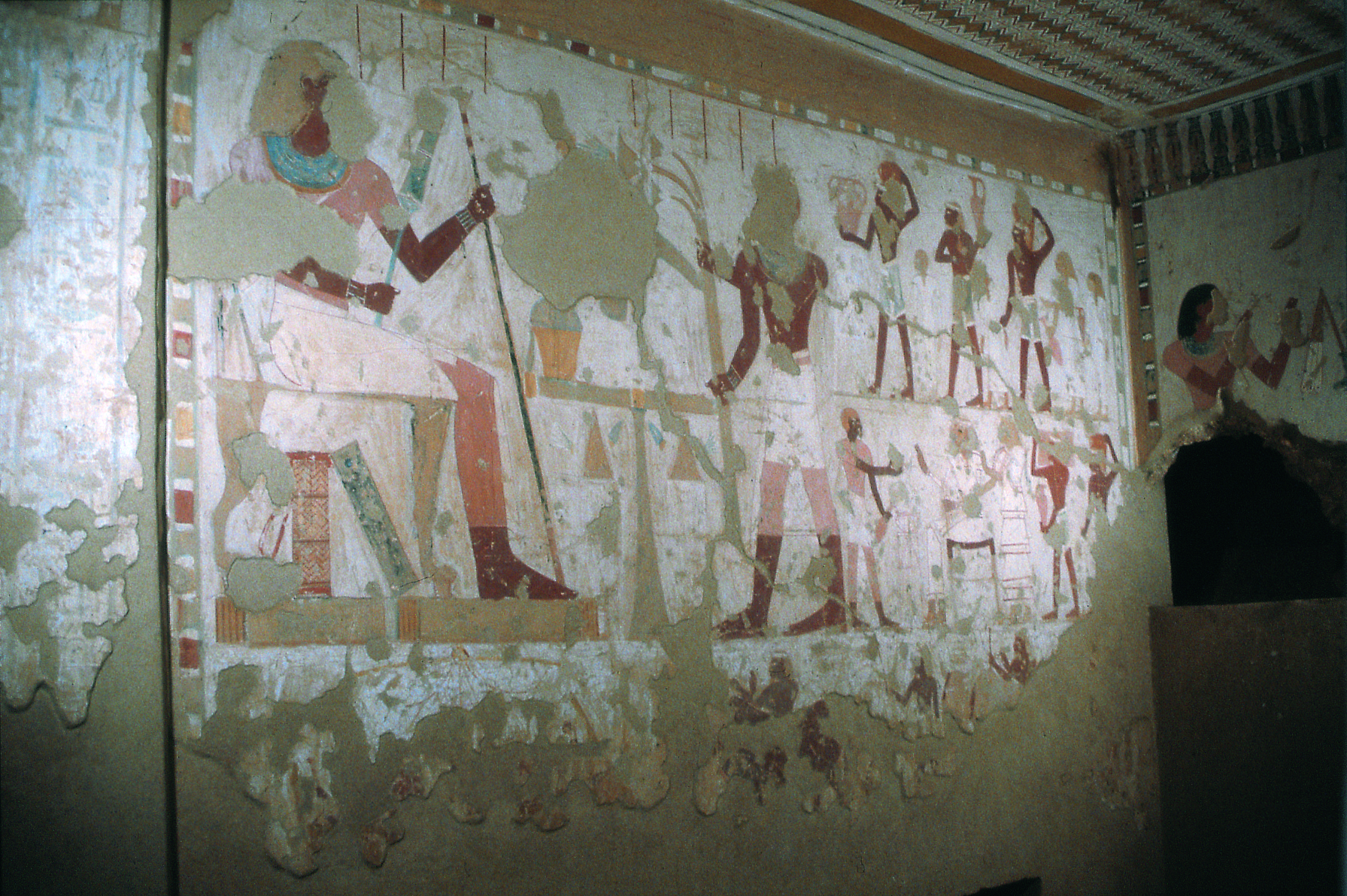

Tomb of Nebamun (TT 17), northern end of Dra Abu el-Naga, Thebes west bank

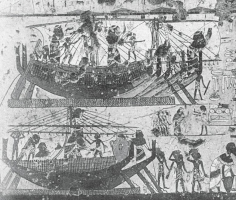

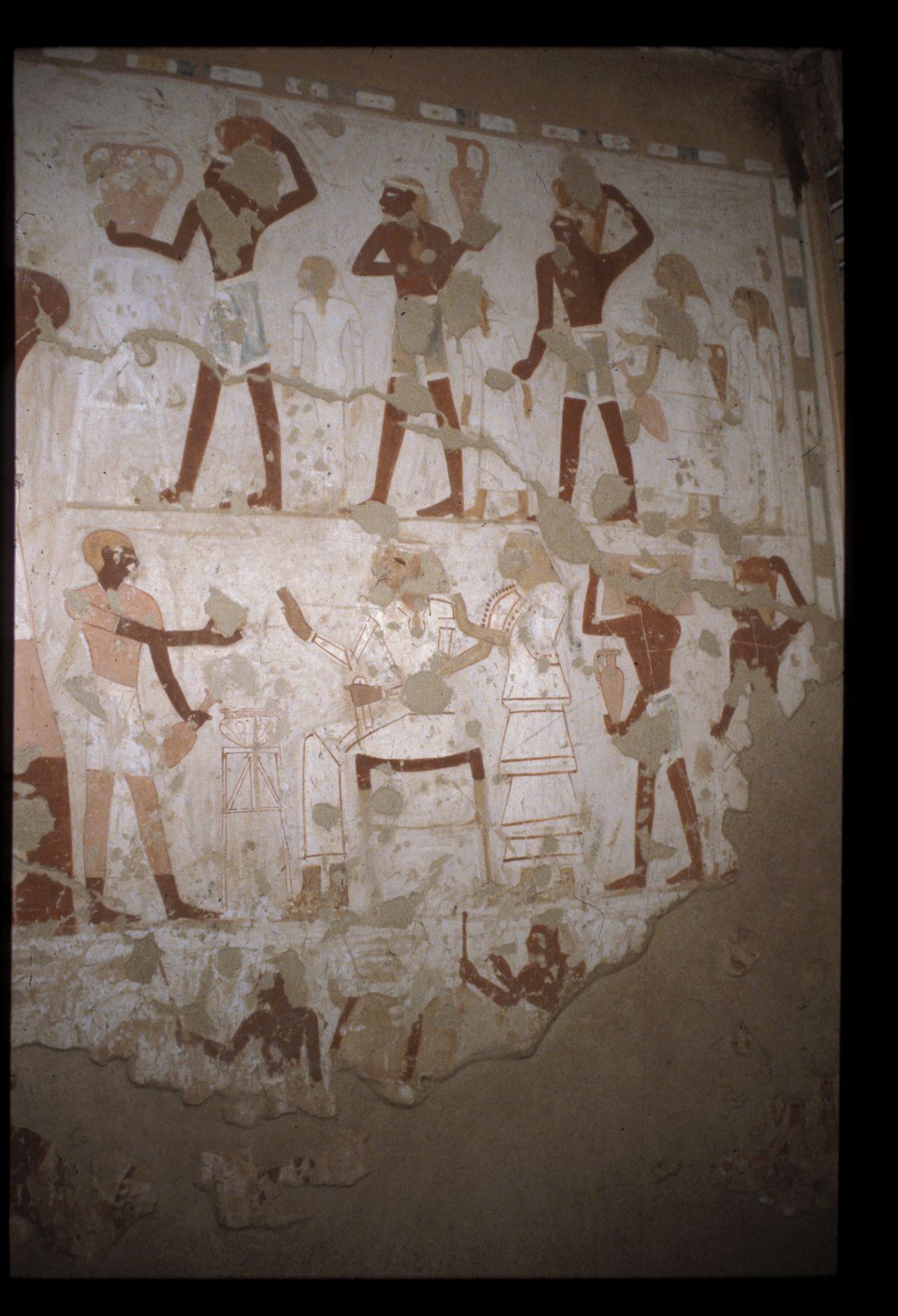

Tomb fresco. Poorly preserved section

TT 17

Allon 2019: 86-87, fig. 2.1b; Basch 1987: 63, no. 110; Emanuel 2014: 31-32, fig. 6; 2017: 125, 127, fig. 8.3; Knapp 2019: 133; Manassa 2013: 93; Mark 2017; Müller 1904: Taf. 3; Säve-Söderbergh 1957: pl. 23; Shirley 2007 (detailed tomb context analysis); Wachsmann 1998: 45-47, figs. 3.7, 3.8, 3.9; 2019: 10, fig. 9a-b

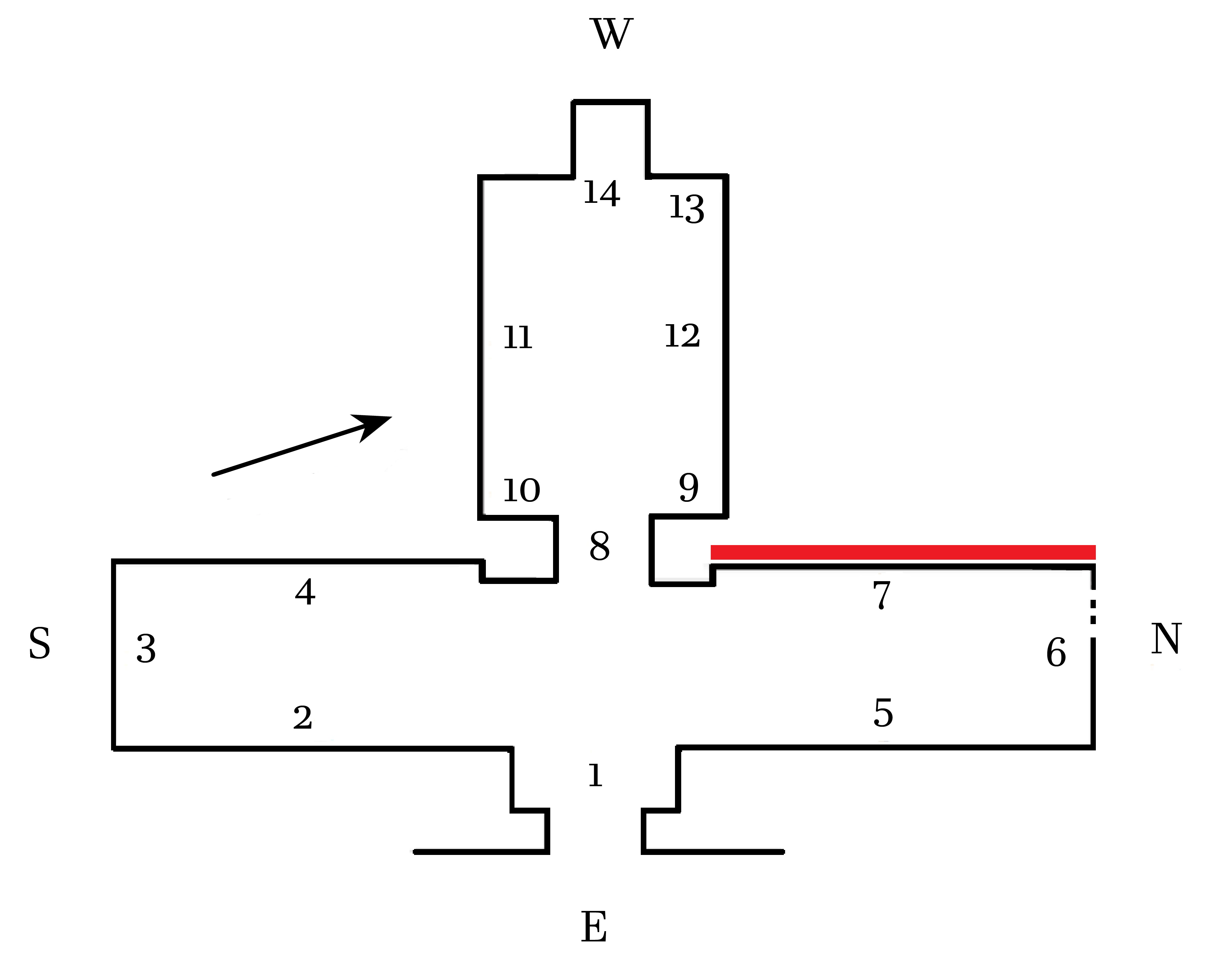

Nebamun was a mid-18th Dynasty elite official who served as royal scribe and physician of the king. The scene containing the Syro-Canaanite ship is located on the north side of the rear (west) wall of the transverse hall (no. 7 on plan). The choice of this placement is of great significance since the scene would have been immediately visible to an observer either looking into or entering the tomb. The information it provides is therefore a great indicator of how the tomb owner wished to represent and showcase himself. The scene depicts Nebamun seated and receiving offerings from his brother, followed by two registers of foreigners behind him amongst which is distinguishable a dignitary and his wife. The bottom register includes a ship and more foreigners leading hump-backed bulls. These foreigners are identified as Syrians based on their features, the objects they carry, the type of bull and the ship itself. This makes the content of the scene unique among tomb representations which typically depict offering scenes involving a family member followed by registers of family and guests. The explanations of this scene oscillate between two general categories, as either evidence for Egyptian doctors in foreign lands or as Syrian dignitaries in Egypt. These disparate readings have hinged on determining whether the ship is arriving or departing, whether the bulls pulling wagons are transporting goods onto or off the ship, and whether the Syrian dignitary is being served by a servant or Nebamun himself. The latest and most detailed analysis of the scene within the broader context of the tomb by Shirley draws several important conclusions (Shirley 2017):

1) The scene depicts Nebamun performing his official duties (holds the staff and sceptre of office, scribal case and palette beneath his chair), in this case involving the meeting with Syrian dignitary.

2) The event takes place in Egypt and Thebes more specifically. In particular, the focal point of the scene involves an Egyptian figure serving the seated Syrian dignitary, the latter thus being in the role of a guest (seated on an Egyptian stool and holding an Egyptian marker of status).

3) "The extremely low number of foreign ships depicted in Egyptian tombs indicates that these are highly unusual scenes that must have been chosen by the tomb owners for very particular reasons. In addition, in all but one of these tombs the scenes are found on the focal and front walls of the transverse-hall."

4) The lower register depicts the departure of the ship from Syria rather than arriving in Egypt. The unfurled sails and the placement of the quarter rudder indicate a departure, with the bulls pulling wagons being used to transport the goods.

5) The visit from the Syrian dignitary and his entourage is portrayed in a way that suggests that it was a recurring part of Nebamun's official duties.

6) The departure of the Syrian dignitary by ship from Syria and his entertainment at a banquet in Egypt (Thebes) indicate that the two episodes were of great personal significance to Nebamun. It is thus likely that the dignitary came at least in part to consult the royal physician specifically. The items transported are thus possibly gifts in exchange for professional services.

Mark has offered a recent re-interpretation of the ship as Egyptian. His arguments are unconvincing, as they rely on discrediting key representational evidence from local Levantine contexts as possibly Egyptian (L15, L18), while also not considering the broader corpus of Levantine ship imagery, notably the Carmel coast graffiti (Mark 2017). More importantly, both the earliest 18th century BC representations of the mnš vessels type as well as the latest known Early Iron Age examples come from indigenous Levantine sources.

Allon, N. 2019. Writing, Violence, and the Military. Images of Literacy in Eighteenth Dynasty Egypt (1550-1295 BCE). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Basch, L. 1987. Le musée imaginaire de la marine antique. Athens: Institut Hellénique pour la preservation de la tradition nautique.

Emanuel, J.P. 2014. “Sea Peoples, Egypt, and the Aegean: Transference of Maritime Technology in the Late Bronze Age-Early Iron Transition (LH IIIB-C),” Aegean Studies 1.1: 21-56.

―――. 2017. Black Ships and Sea Raiders. The Late Bronze and Early Iron Age Context of Odysseus’ Second Cretan Lie. London: Lexington Books.

Knapp, A. B. 2018. Seafaring and Seafarers in the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Manassa, C. 2013. Imagining the Past. Historical Fiction in New Kingdom Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mark, S. 2017. “The Ship Depiction in the Tomb of Nebamun: The First Egyptian Seagoing Ship without a Hogging Truss,” JAEI 16: 68-86.

Müller, W. M. 1904. Neue Darstellungen “mykenischer” Gesandter und phönizischer Schiffe in altägyptischen Wandgemälden. Berlin: W.Peiser Verlag.

Säve-Söderbergh, T. 1957. Four Eighteenth Dynasty Tombs. Private Tombs at Thebes 1. Oxford: Griffith Institute at the University Press.

Shirley, J. J. 2007. “The Life and Career of Nebamun, the Physician of the King in Thebes,” in Z. A. Hawass and J. E. Richards (eds.) The Archaeology and Art of ancient Egypt: Essays in honor of David B. O’Connor. Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 36. Cairo: Conseil Supreme des Antiquités de l’Égypte, pp. 381-402.

Wachsmann, S. 1998. Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

―――. 2019. “On the interpretation of Watercraft in ancient Art,” Arts 8.165: 1-67.