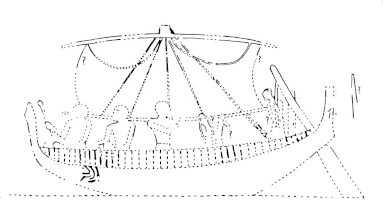

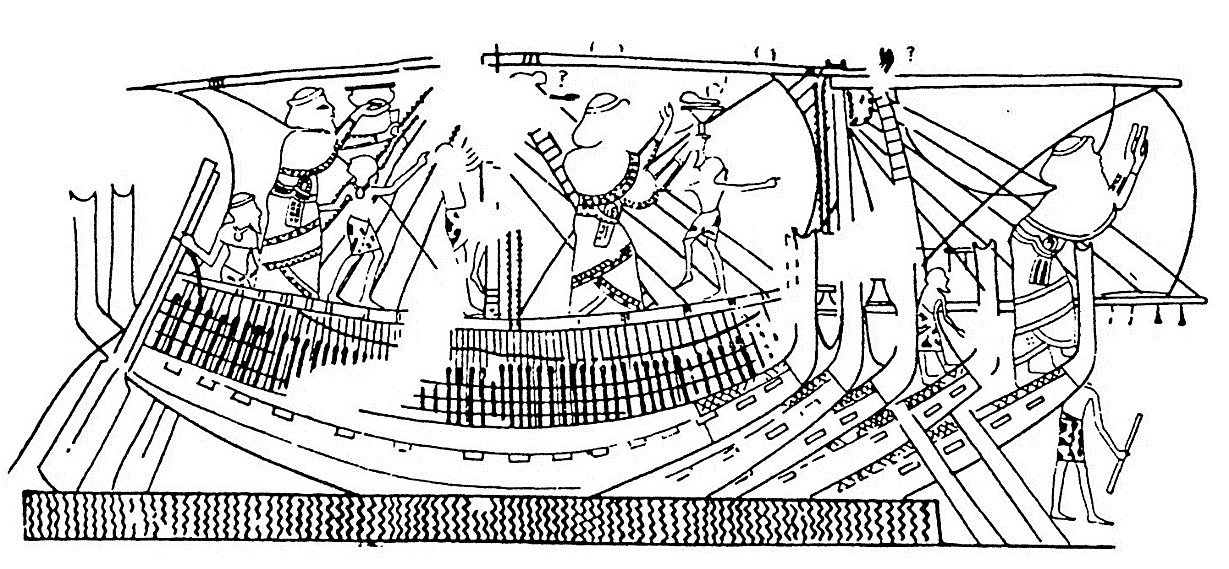

The scene includes a total of eleven

identical ships. Two of these are represented on a much smaller scale in

the leftmost register, and are possibly meant to represent freight

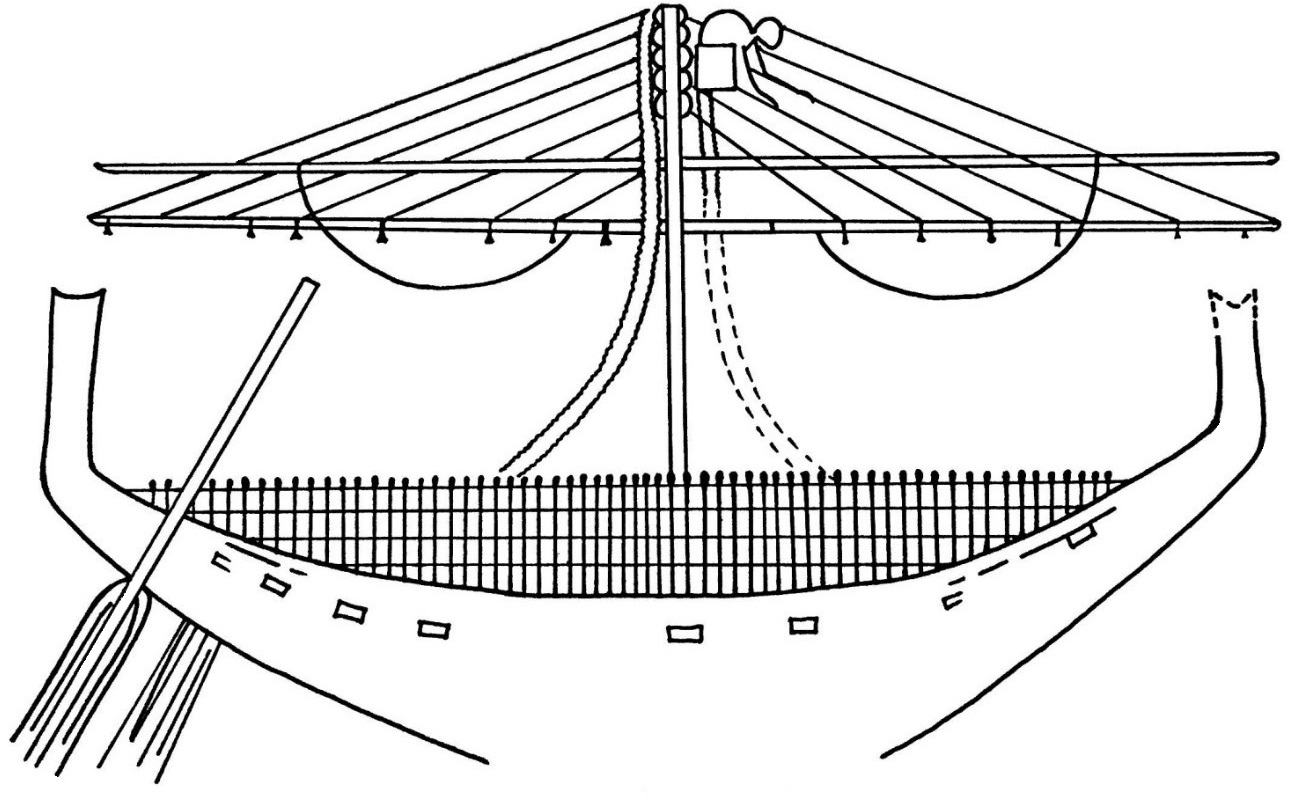

boats. The ships have crescentic hulls with a very strong - most likely

exaggerated - sheer. The vessels of the upper register of the central

section have the most detailed hulls. Of these, the ship depicted in

full closest to the viewer has three strakes delineated by seam lines

and two butt joints. The first butt joint is between the hull and the

stem finial, while the second is located between the two planks in the

middle strake. The remaining four ships staggered behind this vessel

likewise show a butt joint between the stempost and the hull. The other

construction features depicted on these five vessels are a short run of

lacing along the sheer in the bow section, and a line of through-beam

ends which protrude from the side of the hulls below the sheer strake.

The stempost and sternpost are high and symmetrical. They rise

vertically, with a slight hollow of the outer edge and a flat or concave

top. Basch highlights that one of the ships from Daressy's publication

has a widening stempost extremity comparable to Phoenician craft

depicted in EIA Assyrian reliefs. All the vessels have a wickerwork and

post screen running the length of the ship at the sheer. Each vessel has

two quarter rudders with rectangular oar blades and short tillers. No

stanchions are depicted, yet they must be inferred since they would have

been necessary to support the looms. The mast is stepped amidships, with

two ships displaying bindings low on the mast which could be wooldings.

If this interpretation is correct, the mast must have been composite.

The front ship on the central lower register has a square shaped crow's

nest attached on the fore-side of the mast. The remaining ships have

lookouts although the crow's nests themselves are hidden by the rigging.

The vessels have the typical boom-footed LBA rig. The yard is straight,

and was raised and lowered using two halyards that are represented as

thick wriggly lines. Similar to Egyptian practice, these halyards were

tied astern when the sail was raised, thus serving as additional

backstays. Braces are depicted on four vessels. On the ship of the upper

central register, they are tied to the lower mast. Sheets, stays, and

shrouds are not depicted. The stays must be inferred, while the cables

attached to the lower section of the mast may have served as

replacements for the shrouds. Two of the ships have rope ladders running

from the masthead forward to the bow. The series of triangles hanging

from the boom on some of the ships are either toggles for furling the

sail or tassels. Wachsmann argues against Faulkner and Basch that the

boom was hoisted in order to furl the sail. He cites among other things,

the fact that one of the ships shows the boom lashed to the mast.

Merchant Syro-Canaanite fleet

L2

Early 18th Dynasty, reign of Amenhotep III (1390-1352 B.C.)

Tomb of Kenamun, Theban necropolis, Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, Nile west bank opposite of Luxor

The tomb has been covered since the mid-1940s and is now inaccessible. Study limited to photos and copies of the scene.

TT 162

Basch 1987: 63-64, nos. 111-114; Daressy 1895; Davies 1930; 1963: 14-18, pl. XV-XX; Davies and Faulkner 1947; Dewachter 1980: 69-73; Knapp 2019: 132-133; Köster 1923: no. 11; Mark 2017: 74-76, 78-79, 82, fig. 3; Polzer 2011: 360; Pomey 2015: 11, fig. 24; Pulak 2008: 300-301, fig. 98; Shirley 2007: 389. Fig. 7a; Vinson 1994: 40-41, fig. 28; Wachsmann 1998: 42-47, figs.3.2-3.6, 313-14, fig. 14.6; 2019: 5-6, 51-53, figs. 4a-b, 5a-b, 51b, 52, 53; Yasur-Landau 2018: 554-555, fig. 30.1; Yon and Sauvage 2015: 77, 87, fig. 3b

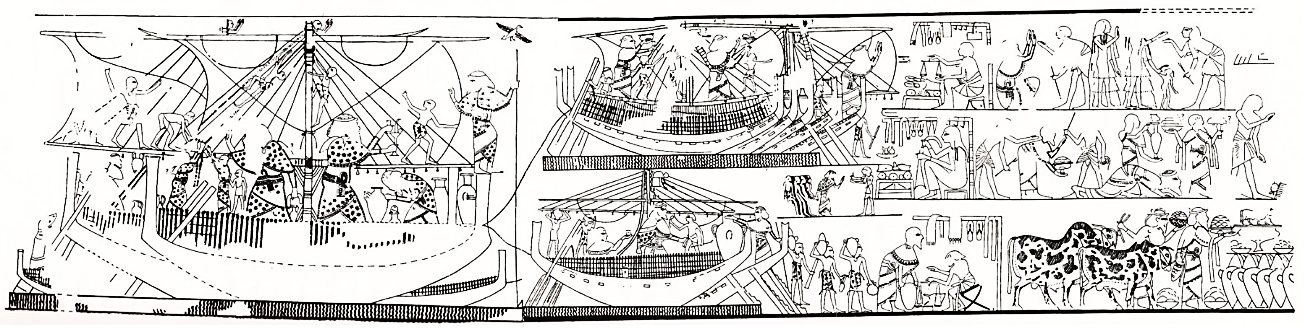

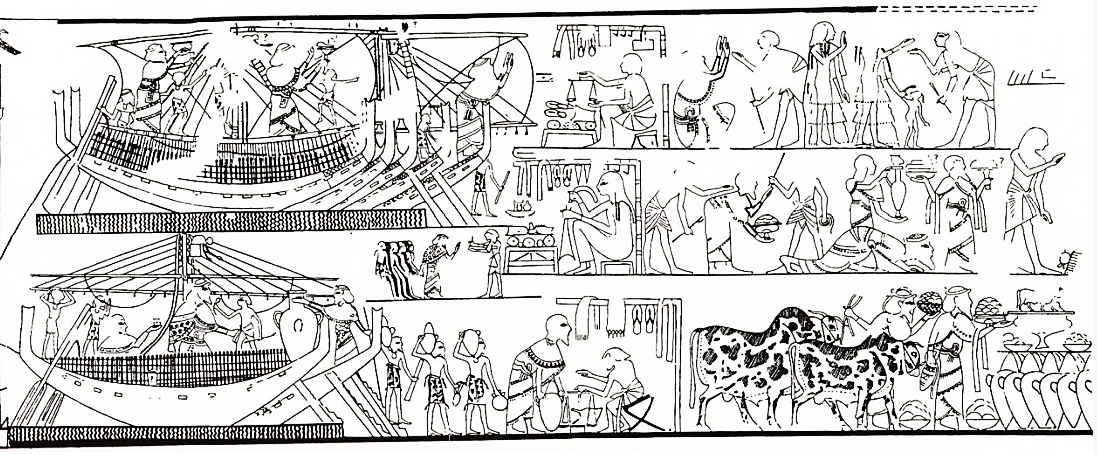

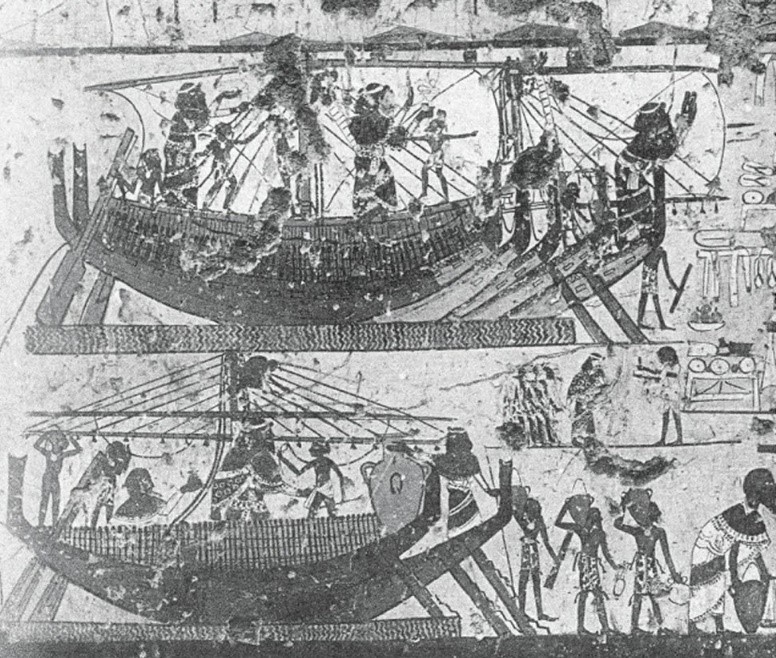

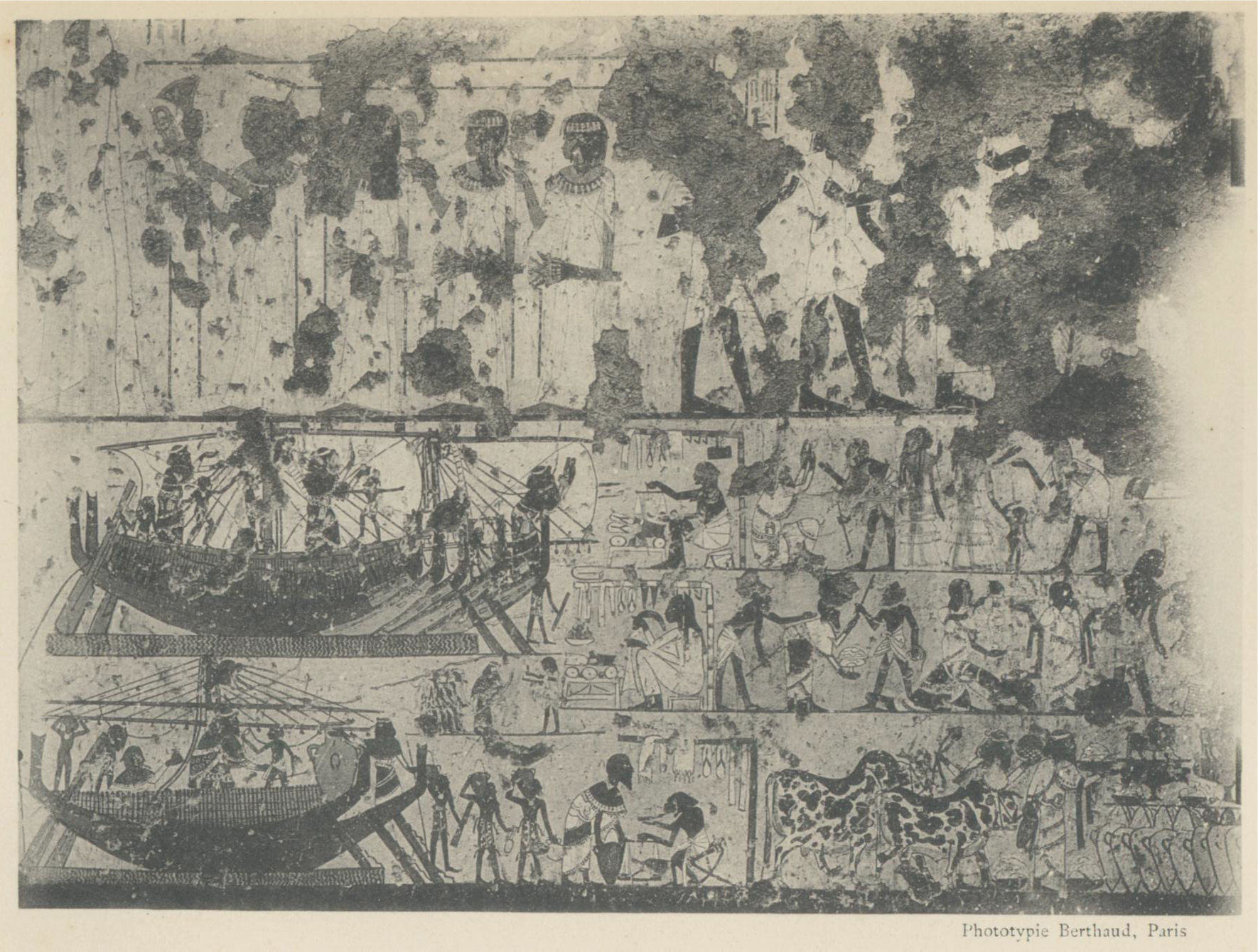

Kenamun was the mayor of Thebes, superintendent of the granaries of Amun, and royal steward. He also enjoyed the much coveted role of foster brother of the king thanks to his mother Amenemipet which was a wet nurse of Amenhotep III. As the mayor of Thebes, Kenamun's duties would have included managing the arrival of foreign ships. His tomb provides the most detailed Egyptian representation of Syro-Canaanite ships, located on the front wall of the transverse-hall. The scene is divided into three parts: a single register with four ships on the left, two registers with seven ships docked at an Egyptian port in the center, and three registers depicting a market scene at the harbour on the right. The scale of various figures in the scenes varies according to their status following Egyptian convention. The crew aboard the ships is identified as Canaanite based on typical identifiers used in Egyptian iconography such as bearded facial features, distinctive dress and hairstyle, and the primary cargo of Canaanite jars.

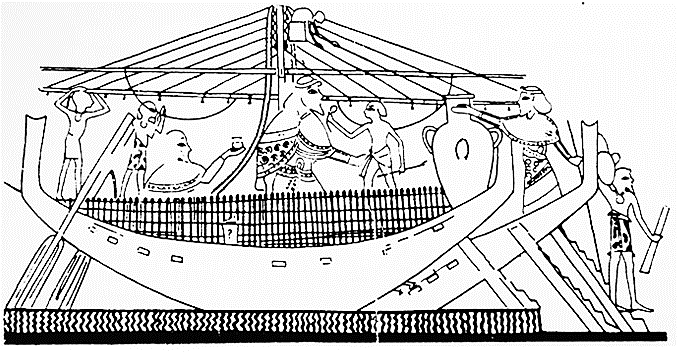

1) left section: two large ships under sail occupy the full height of the scene. The large ship closest to the viewer is depicted in full, while only the stern of the second one is visible behind it. Two smaller craft are depicted on either side, connected to the large vessels by ropes. The figures in the scene are depicted in three distinct scales of decreasing size. On the complete ship, the two men standing on either side of the mast are the largest in stature and therefore highest in rank, most likely the chief merchants in charge of the venture. The left one appears to be calling out or providing orders, while the right one is conducting a ritual in thanks for a safe arrival. Both are dressed in the typical Syrian attire classified by Pritchard as type C, which begins in the last quarter of the 15th century and continues well after the 18th Dynasty. It consists of a long undergarment reaching in folds to the ankles, with a tasselled belt and a cape worn loosely over the shoulders. Occasionally as is the case here, the undergarment has long sleeves (Pritchard 1951: 41). On a slightly smaller scale are two more individuals in the same distinctive garb. One of them is assisting with the ritual, handling a small amphora for the libation, while the other stands on the stempost and appears to be holding a sounding and giving orders. The remainder of the crew is depicted in the smallest scale. With the exception of a pair of individuals tugging at the lifts at the stern which also wear Syrian robes, the ordinary deck hands are clad in loin cloths only. Some of them wear a round medallion very similar to those found on the Uluburun ship. Most of these crewmen are shown climbing on the ship's rigging, while one sits in the crow's nest atop the mast.

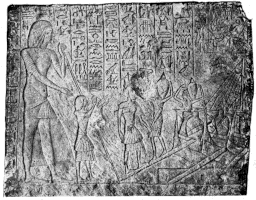

2) middle section: two registers comprising a group of five and two vessels respectively, shown docked at a quay with their gangways deployed. The figures and the activities aboard these vessels are similar to the left register, with the prominent Syrian merchants performing arrival rituals. The ship closest to the viewer on the lower register has a large pithos at the bow, very similar to the ships from the Iniwia tomb. Several crewmembers are shown in the process of unloading cargo. Each carries a Canaanite jar on their right shoulder and a smaller object in their left hand, one of which is a pilgrim flask. In the upper right corner of the lower register, a Syrian merchant is bringing forward a group of men (probably slaves) in front of an Egyptian scribe holding a tablet.

3) right section: a bustling market scene divided in three registers showing both local and international commerce. Men and women are shown sitting in stalls covered by awnings, either selling commodities (textiles, sandals, foodstuffs) or weighting products. The stalls appear to be well-established, professional stands equipped with scales and all manner of commerce implements, suggesting a permanent market at the port. Both official trading through the agency of high placed officials such as Kenamun and small-scale private trading are represented. On the lowest register, some of the merchandise unloaded from the ships is taken in front of an official operating scales while seated on a stool. The cargo consists primarily of Canaanite jars, but also two humped bulls of a foreign breed, a pilgrim flask, metal vessels, and bowls filled with smaller objects.

The artist clearly lacked understanding with regards to the rigging of the vessels. Wachsmann points out several problematic details: 1) the lifts are not connected to the mast in three examples, instead being tied to the yard at both ends; 2) in one case where the yard has been lowered, the lifts are in the shape of pendant arcs, whereas they should be drawn stretched while supporting the yard. These mistakes indicate that the artist was confused about their purpose. There are furthermore several Egyptianizing hybrid elements, including the lacing near the bow of the craft, the single row of through-beams, and the straight rather than curved yard. In addition, distortion of the hull is also likely since Egyptian artists had the tendency to exaggerate sheer lines, possibly due to a desire to show most of the vessel above the waterline. Finally, there are internal inconsistencies from one vessel to another. This is most evident in the upper register of the middle section of the composition, where the hulls are markedly shallower and have a much more pronounced concave sheer. Another variation in rendering is observable in the post terminals, which are concave on the ships of the middle section but flat on the left one. Despite these problems, a Syro-Canaanite identification is not in doubt due to the very clear identification of the ship's crew based on their attire, beard and coiffure, as well as the cargo. The vessels are overall remarkably similar to the Nebamun ship, and display certain distinctive feature notably the form of the posts and the presence of a crow's nest. Mark claims that the Kenamun vessels are an accurate representation of Syrian ships in an attempt to mark them as distinct from the Nebamun ship which he wants to read as Egyptian (Mark 2017: 82). This interpretation is unconvincing in the context of the broader corpus of mnš type representations.

Basch, L. 1987. Le musée imaginaire de la marine antique. Athens: Institut Hellénique pour la preservation de la tradition nautique.

Daressy, G. 1895. “Une flotille phénicienne d’après une peinture égyptienne,” Revue Archéologique sér. 3 (t. 27): 286–92.

Davies, N. de G. 1930. “The Egyptian Expedition: The Work of the Graphic Branch of the Expedition,” BMMA 25 (pt. 2, December): 29-42.

Davies, N. de G. and R. O. Faulkner. 1947. “A Syrian Trading Venture to Egypt,” JEA 33: 40–6.

Dewachter, M. 1980. “Un nouveau ‘fils royal’ Qenamon,” Revue d’Égyptologie 32: 69-73.

Knapp, A. B. 2018. Seafaring and Seafarers in the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Köster, A. 1923. Das antike Seewesen. Berlin: Schoetz & Parr-hysius.

Mark, S. 2017. “The Ship Depiction in the Tomb of Nebamun: The First Egyptian Seagoing Ship without a Hogging Truss,” JAEI 16: 68-86.

Polzer, M.E. 2011. “Early Shipbuilding in the Eastern Mediterranean,” in A. Catsambis, B. Ford, D.L. and Hamilton (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 349-378.

Pomey, P. 2015. “Navires et construction navale en Égypte ancienne,” in : B. Argémi and P. Tallet (eds.) NeHeT 3. Entre Nil et mers : La navigation en égypte ancienne. Actes des rencontres de Provence Égyptologie Musée Départemental Arles Antique le 12 avril 2014, pp. 1-29.

Pulak C. 2008. “The Uluburun Shipwreck and Late Bronze Age Trade,” in J. Aruz, K. Benzel, and J.M. Evans (eds.) Beyond Babylon: Art, Trade, and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium B.C. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 288-305.

Shirley, J. J. 2007. “The Life and Career of Nebamun, the Physician of the King in Thebes,” in Z. A. Hawass and J. E. Richards (eds.) The Archaeology and Art of ancient Egypt: Essays in honor of David B. O’Connor. Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 36. Cairo: Conseil Supreme des Antiquités de l’Égypte, pp. 381-402.

Vinson, S. 1994. Egyptian Boats and Ships. Shire Egyptology 20. Buckinghamshire: Shire Publications.

Wachsmann, S. 1998. Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

―――. 2019. “On the interpretation of Watercraft in ancient Art,” Arts 8.165: 1-67.

Yasur-Landau A. 2018. “The Archaeology of Maritime Adaptation,” in: A. Yasur-Landau, E.H. Cline and Y.M. Rowan (eds.) The Social Archaeology of the Levant from Prehistory to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 551-570.

Yon, M. and C. Sauvage. 2015. “La navigation en Méditerranée orientale à l'Âge du Bronze Récent,” in : B. Argémi and P. Tallet (eds.) NeHeT 3. Entre Nil et mers : La navigation en égypte ancienne. Actes des rencontres de Provence Égyptologie Musée Départemental Arles Antique le 12 avril 2014, pp. 73-103.