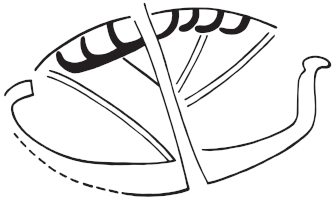

Altar graffiti (L6): the topmost and largest of the four graffiti is

also the most detailed. This ship can be confidently identified as

facing left, thanks to the presence of two quarter rudders, one of which

has an attached L-shaped tiller (T). It has a flat hull with a high

incurving sternpost. The curving stempost is shorter, and bends sharply

inward at the top - almost at a straight angle - running parallel to

the hull and ending in a flaring extremity which Artzy describes as a

"fan." The mast is roughly amidships, with three oblique strokes

crossing it which are possibly shrouds and a sail above (S). There are

possibly two oars in the bow section which were rendered with deep

incisions. Their orientation and the fact there are only two is however

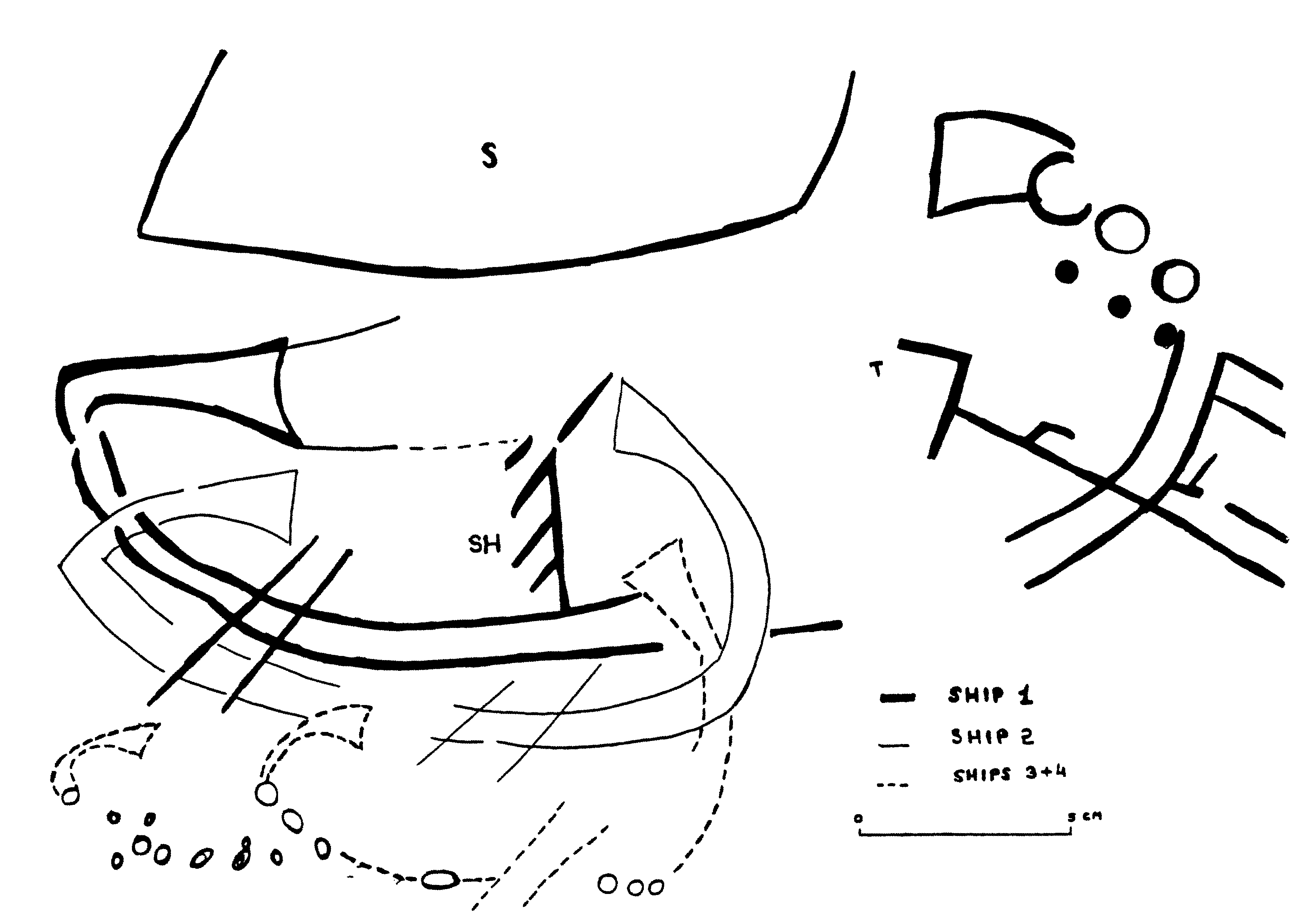

curious. The remaining three ships are of smaller, progressively

decreasing proportions, but are otherwise very similar in shape and are

clearly meant to depict the same type of vessel. Unlike the largest ship

however, these show only the hulls, with the exception of ship 2 which

also possibly has two oars. When compared separately, it becomes clear

that the sternposts and the flaring bow devices of the four ships are

similar albeit not identical. This is to be expected given the medium as

well as some of the accommodations that the artist had to make in such

an overlapping composition.

Quartz pebble graffito (L7): the ship is very small (< 2 cm in

width) making its details difficult to discern. It has two rounded ends

and high posts, with the right one slightly higher. Artzy interprets the

ship as facing right, and notes that the stempost has an everted

extremity which possibly consists of an animal-headed device. The

sternpost does not seem well defined.

Portable altar ship graffiti

L6-L7

End of 13th- beginning of 12th century B.C.

Akko, Area H (square L-7)

Altar: 30 x24 x 26 cm

Portable stone altar; quartz pebble

Artzy 1984: 59-64; 1987: 75-83, figs. 1,2; 1988: 182, fig. 1; 1994: 33; 2003: 232-33, figs. 1, 10; 2006b: 117-18, figs. 2, 3; Knapp 2019: 126-127, fig. 28

The earliest evidence of occupation on the flat surface atop Akko's rampart dates to the end of the 13th and the very beginning of the 12th century B.C., with all three areas examined (H, PH and AB) uninhabited throughout the Amarna period despite written evidence attesting to the existence of the site, which must have been located elsewhere during the LBA. Each of these areas varies in the nature of human activity: area AB has been identified as an industrial zone (furnace, thick ash layers), area H is defined as cultic in nature (altar), and area PH as a living quarter.

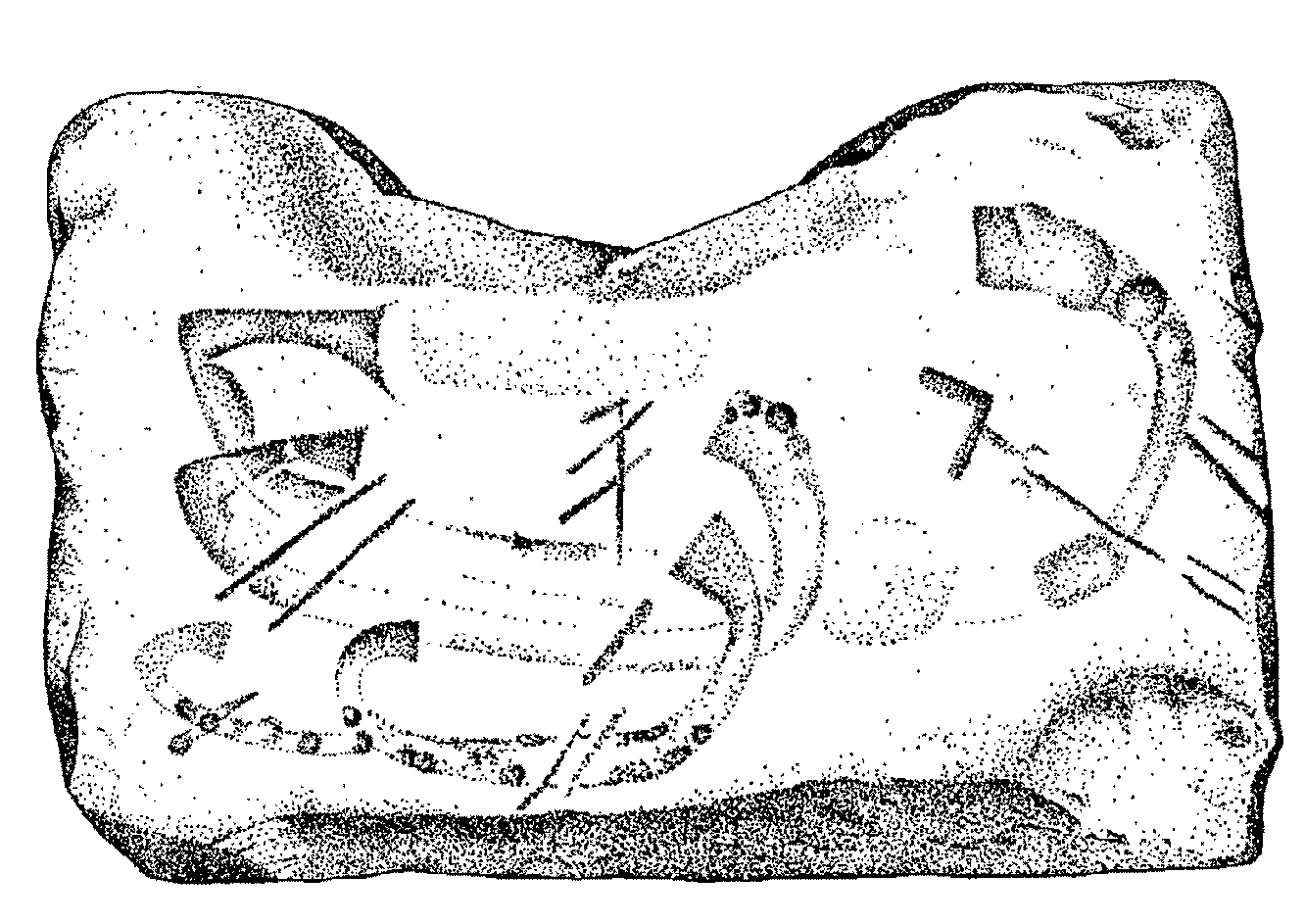

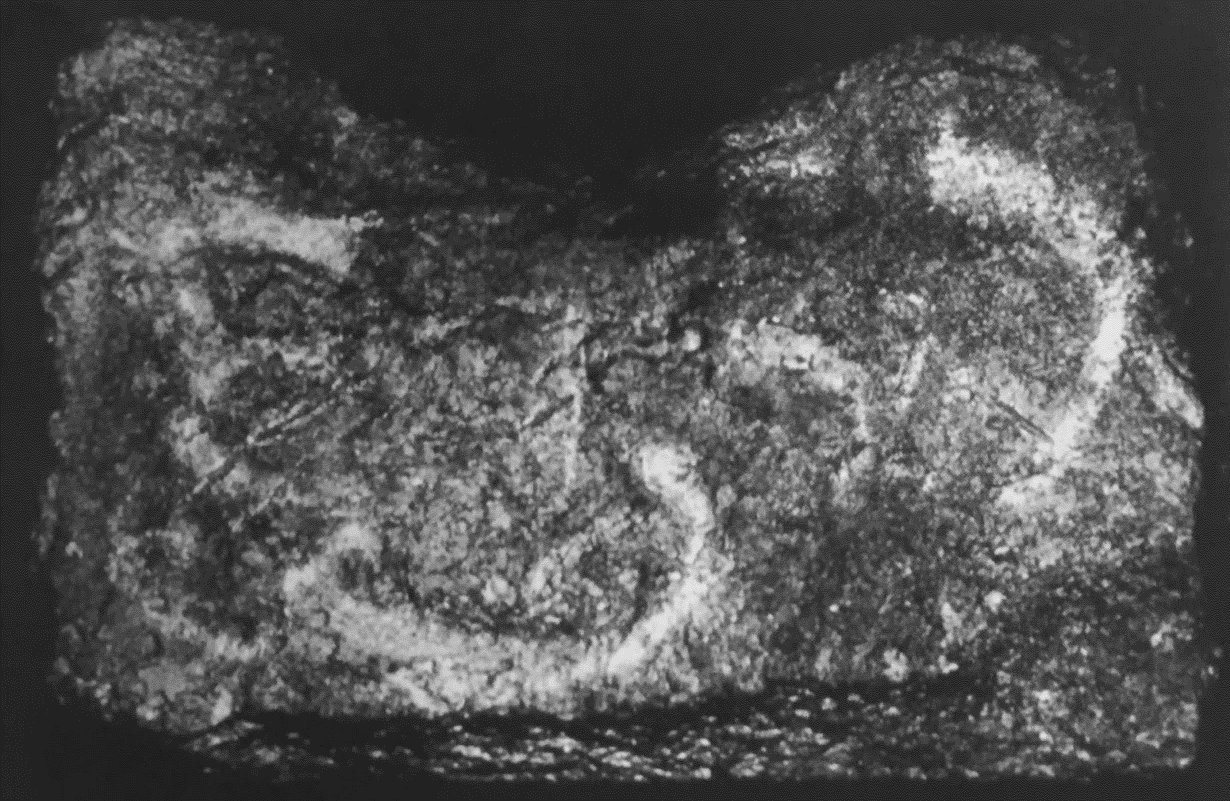

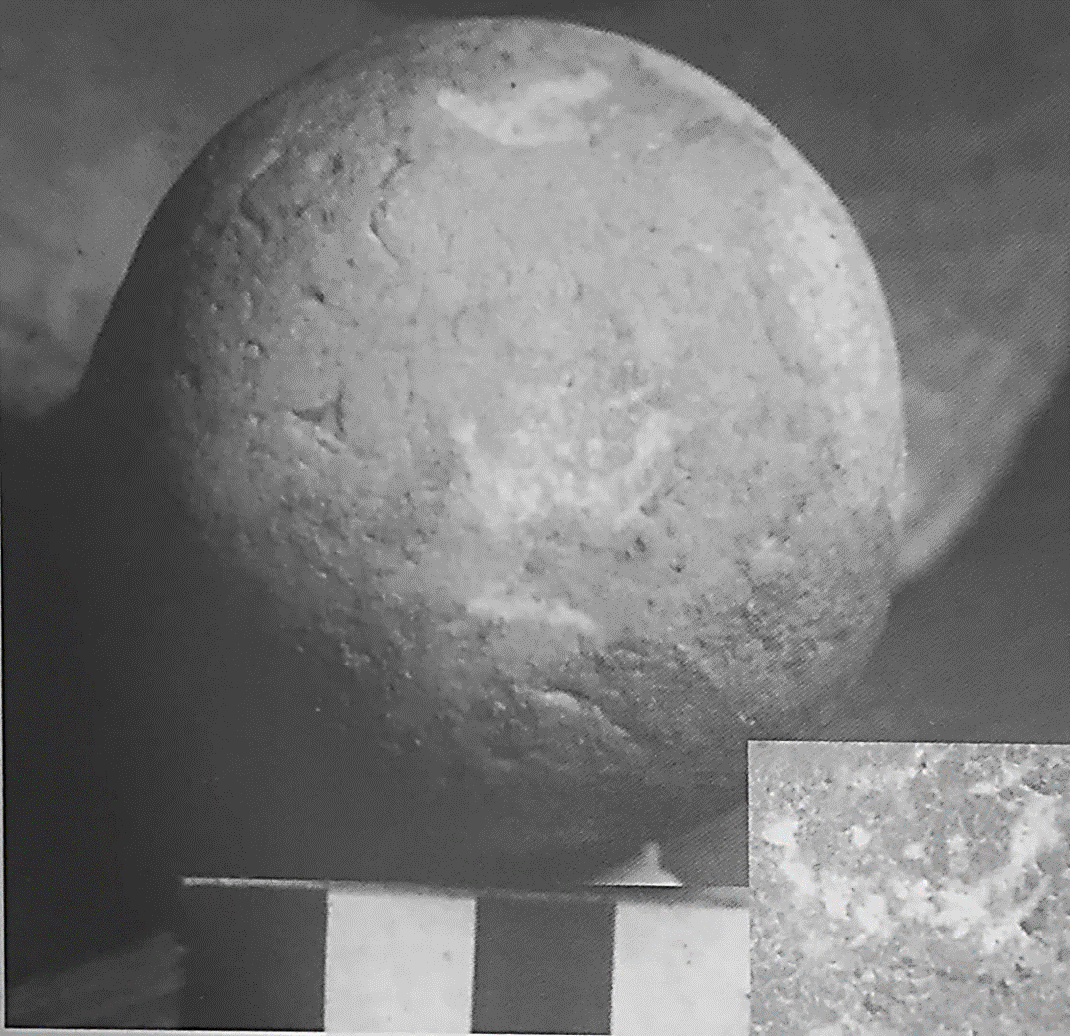

The altar was found in Area H, about 5 m away from a pit that contained fragmentary pottery (storage jars, miniature storage jars, and a krater) which had been thrown and smashed by stones. It was connected by a row of stones to a partially stone-lined bothros containing large amounts of ash and some sherds. On top of the altar was more ash and three pebbles roughly the size of an orange, bearing representations, including a small ship, a dolphin, a bird (?), another fish (dolphin or tuna), and additional signs which have not been deciphered. The pebble with the engraving of the tiny ship, a fish and possibly a bird is made of quartz, a rock which is not indigenous to the region.

Artzy notes that the altar is oddly shaped, especially its base, which combined with its small size suggests that it was portable (Artzy 2003: 232; 1987: 76). If this hypothesis is correct, it is possible that the altar was in a secondary use, and might have originally served aboard a ship. The widest, front face of the altar bears the graffiti of four ships of varying sizes superimposed on one another in an integrated composition. These decrease in size from top to bottom, with the largest one spanning nearly the entire width of the altar. The smallest ship on the bottom left appears incomplete, with its stern missing. As the graffito overlaps with the third ship at this location, it is possible that the stern simply became indistinguishable when the two were superimposed. The artist used multiple engraving techniques, including grooving, drilling, and plain incisions. Much of the biggest ship was incised, including the mast, brails, oars, tiller and lower rudder. Grooving was used to highlight the stem of the ships, while the hulls were rendered by drilling.

The fan-shape of the stempost device which Artzy has

stressed at great length is perhaps overemphasized. She concedes herself

that the stern extremity of the ships also has a triangular end, but

notes that it is not accentuated in the same manner. She argues that

"[...] the engravers took great care in the representation of the

fans. The clear-cut formation and the depth of the fans show that they

were of paramount importance to the artists" (Artzy 1987: 77). Finally, she notes

that the proportions of these "fans" are difficult to make sense from a

technological point of view, leading her to hypothesize that they were

purposefully exaggerated in order to accentuate their ritual importance.

There are discrepancies however between the two drawings available, with

some of the extremities not flaring nearly as much as one would gather

from the description, especially for the smaller ships. The photograph

does not help clarify this point unfortunately so a re-examination is

warranted. The one secure observation that can be made is that the ships

have two clearly rounded ends with incurving extremities, with the

sternpost decidedly higher and its inward curve less pronounced, while

the stempost has a much more exaggerated, sharp inward bend. As such

these ships are clearly different from contemporary Aegean type, with

the bow projection and vertical stempost conspicuously absent.

The

artist has made certain concessions due to available space and the

nature of the composition. The largest ship 1 was thus given

considerably more details, while the rest were limited to the hull

outline only. This also explains why so few oars are depicted - only

two for ship 1 and 2 respectively - as the addition of more would have

greatly impacted the clarity of the composition which is already

cluttered due to the superimposition.

Artzy, M. 1984. “Unusual Late Bronze Ship Representations from Tel Akko,” MM 70: 59-64.

―――. 1987. “On Boats and Sea Peoples,” BASOR 266: 75-84.

―――. 1988. “Development of War/Fighting Boats of the Second Millennium B.C. in the Eastern Mediterranean,” RDAC: 181-86.

―――. 1994. “On boats, on Rocks and on ‘Nomads of the Sea,’” CMS News 21.

―――. 2003. “Mariners and their Boats at the end of the Late Bronze and the beginning of the Iron Age in the Eastern Mediterranean,” Tel Aviv 30: 232-246.

―――. 2006b. ““Filling in” the Void: Observations on the Habitation Pattern at Tell Akko at the End of the Late Bronze Age,” in A. M. Maeir and P. de Miroschedji (eds.) “I Will Speak the Riddles of Ancient Times.” Archaeological and Historical Studies in Honor of Amihai Mazar on the Occasion of his Sixtieth Birthday. Vol. 1 Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 115-122.

Knapp, A. B. 2018. Seafaring and Seafarers in the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean. Leiden: Sidestone Press.