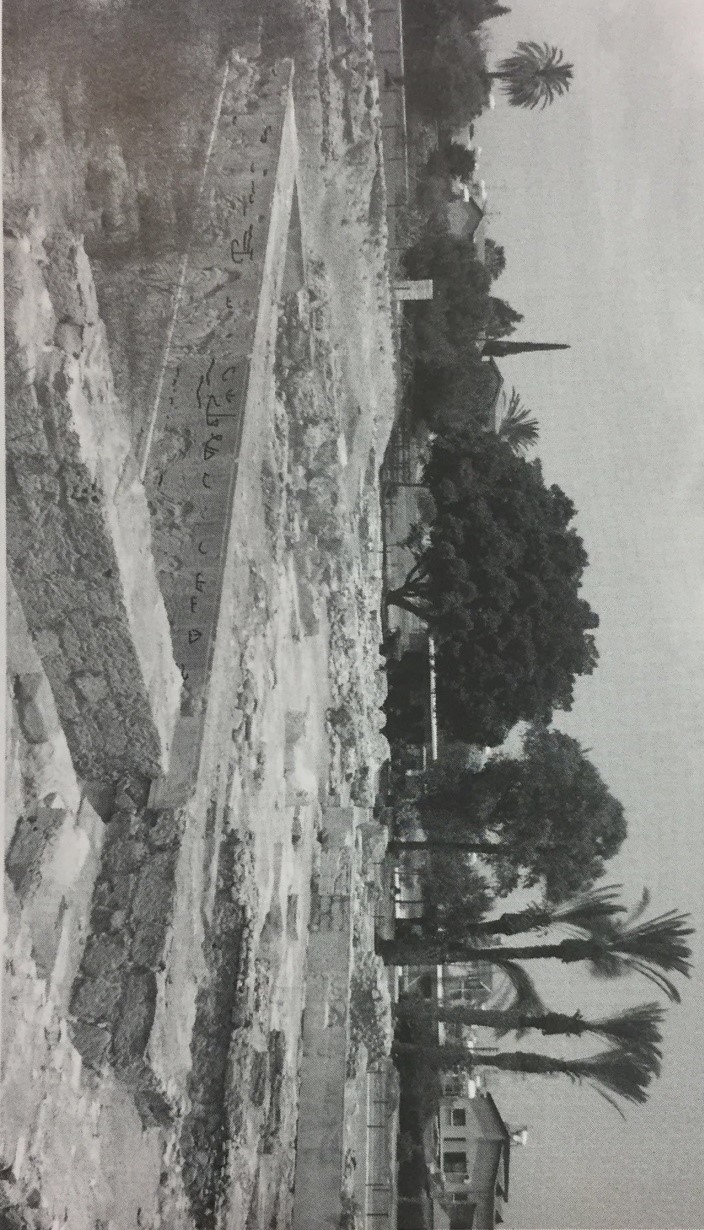

The earliest architectural remains from Area II

date to the LC IIC (1300-1190 B.C.), comprising two cult structures in

close proximity to each other, namely temples 2 (14.5 x 9 m) and 3 (6.75

x 4.15 m). After a brief period, a large-scale destruction of the site

initiated an impressive architectural program that completely rebuilt

the sacred precinct, now comprised of a vast sacred complex delimited by

the city rampart (LC IIIA, 12th century B.C.). During this

reorganization, temples 4 and 5 were added, while temple 3 gave way to a

vast open space (Temenos A). With the exception of the poorly preserved

temple 5, all buildings were built using ashlar masonry. This includes

the largest and most important structure of the precinct - temple 1 -

which was accessed through a monumental porch that opened to a large

court (Temenos B). Temple 1 was the focal point of the precinct, as

suggested by the exceptional architectural quality as well as its

commanding position vis à vis a metallurgical quarter (Northern

Workshop), to which it enjoyed direct access through a gate in its

northern wall. The building's size alone (35 x 22m) makes it one of the

largest monuments on the island known from this period. Temple 1

dominated the precinct not only in size and monumentality but also in

height, as it lies at the highest point of the bedrock in Area II. The

location of the city wall to the north and east as well as the workshops

on the west meant that the southern façade would have been the most

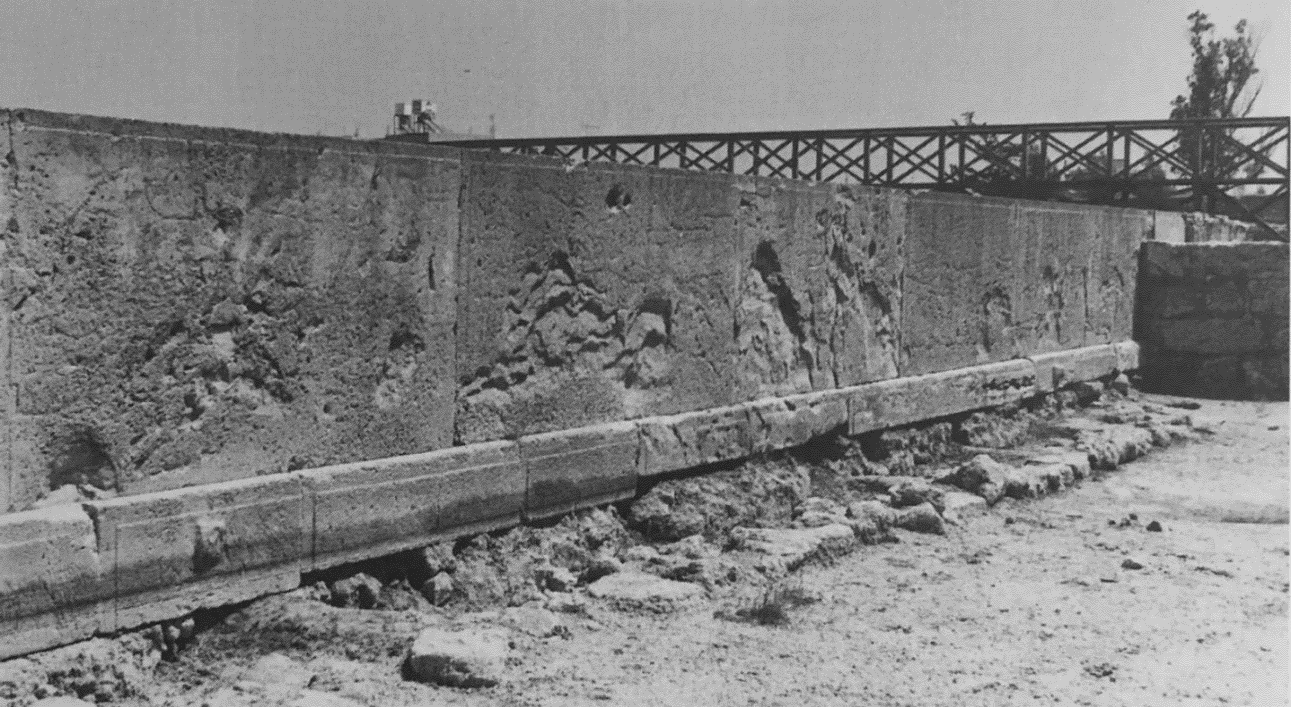

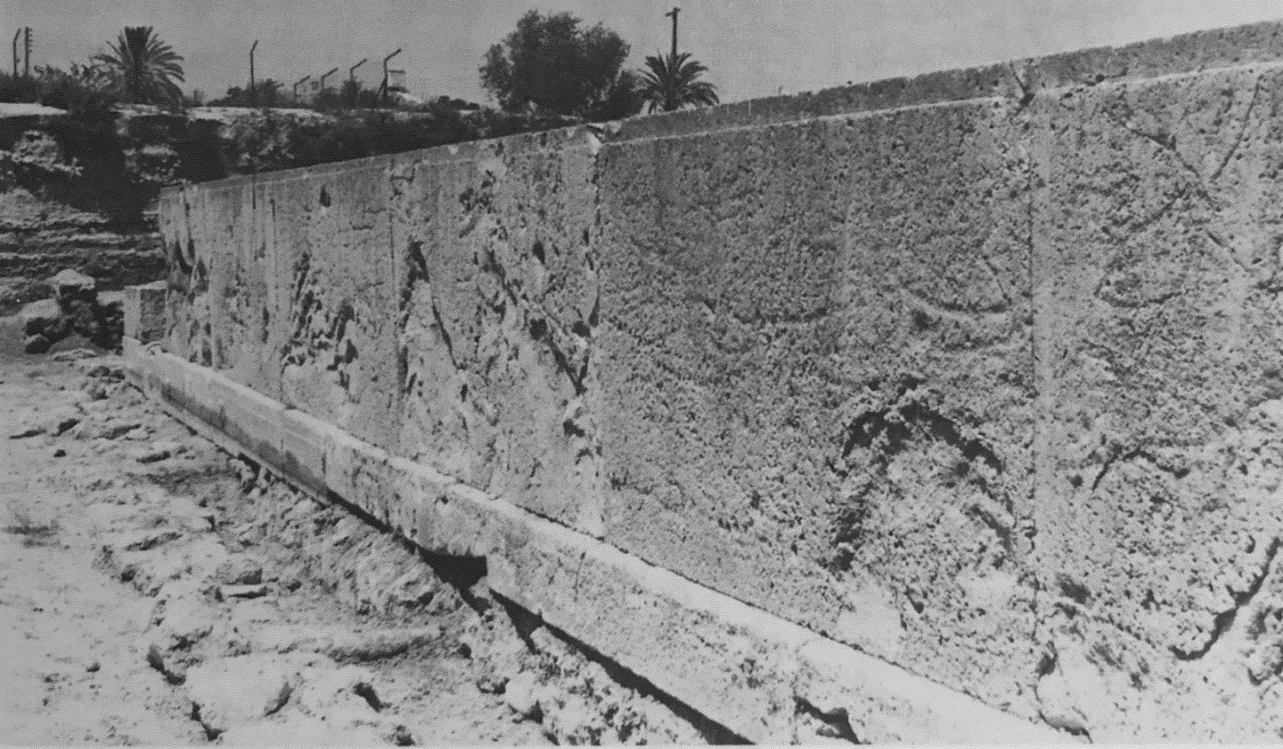

visible and thus the most important. The main internal approach to the

precinct was thus from the south toward temples 1 and 2. The excavators

stress that "the full effect of the massive ashlar orthostats of the

south wall of temple 1 cannot be fully appreciated at close quarters,

even standing at the southern edge of the street. A more distant

perspective is required; a fact which is not likely to have escaped the

notice of the temple architects who were quite clearly aware of the

public presentation of their building"(Karageorghis and Demas 1985: 90).

The monumental restructuring phase represented by Floor II was

eventually destroyed by an earthquake and flooding. In the original

publication of the site, the excavators argued that this was followed by

a brief rebuilding phase (Floor I, 1050-1000 BC), after which the temple

complex at Kathari was considered to have been abandoned for a

significant time of about a century and a half. A recent in-depth

re-examination by Smith however has shown that this gap in occupation in

fact did not occur, as evidenced by several contradictions in the

depositional, structural, and ceramic evidence. Smith notes that the

episode of destruction resulting in a layer of alluvium and sandy soil

above Floor I is similar to that observed after Floor II, with both

representing localized flooding rather than gradual silting up as would

be expected of an abandonment. She furthermore highlights that as with

the deposits following Floor II, the alluvial debris above Floor I do

not cover the entire site but instead are found primarily in the

northern part, just south of the city wall and temple 4. These deposits

are no deeper than the previous phase, which shows the destructions are

structurally similar and indicate episodes of periodic catastrophes

followed by clean-ups and rebuilding. This is indicated by the fact that

in areas farthest from the city wall and the source of the flooding, the

subsequent Floor 3 is not separated from Floor I but instead lies

directly on top of it. This was true for both flooding episodes, with

the depth of alluvial deposits decreasing with the distance from the

city wall. It thus appears that the intervening walls of Temple 1,

Temenos A and Temple 4 lessened the amount of wash reaching the

southernmost parts of the site. Nonetheless, the severity of the

flooding after Floor I seems to have been greater and damaged more of

the site probably due to the already weakened city wall from the

previous earthquake. This overall reconstruction of repeated earthquakes

and flooding is supported by recent corings from the harbour, which

indicate that the area was subjected to sudden changes caused by

tectonic uplift from the LBA onwards rather than a regular sea level

rise. Finally, Smith's re-examination of the pottery assemblage likewise

showed ceramic continuity from Floor I to 3.

The amended dating of Floor I has thus been changed to 1000-850 BC,

which significantly alters our understanding of the temple complex which

clearly remained in use throughout the EIA. During Floor I, the repairs

and alterations to Temple 1 were now made using sandstone rather than

the limestone from earlier periods. Unfortunately, pre-Floor 3 surfaces

inside temple 1 are missing, possibly due to flooding which may have

wiped out many of the earlier deposits. During this time, part of the

city wall was abandoned - in particular tower C, while other parts were

repaired. Changes were also made in the form of an opening for access

from the north, the effect of which was increased access to the harbour

area. Finally, the connection between the metal workshops to the north

and Temple 1 was closed off, blocking access to the north. This was

possibly a measure to prevent flooding. The western workshop area

meanwhile remained in use, but apparently ceased its previous production

of textiles, with the addition of a large oven signalling a new

industry. In the southeast, courtyard C was raised to cover one of the

older steps into the building. Temple 2's importance appears to have

diminished, but its design along with that of Temples 4 and 5, the

temenos areas and the courtyards retained the same overall arrangement

of the earlier period.

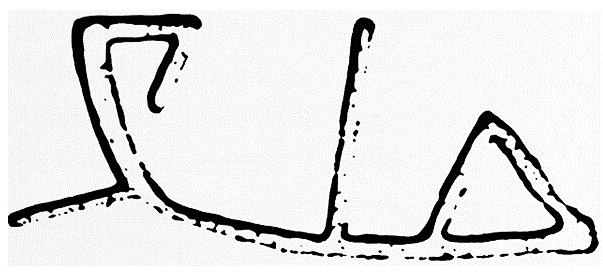

The biggest change however occurred in Temple 4, the interior of which

was considerably altered during this phase following significant

structural damage from the flooding episode. The raising of the floor

level first meant that much of the earlier features which had been part

of the Floors III-II were now covered. In their place, an impressive

built altar was placed near the centre of the main hall, comprised of

two elements of different construction and function: a hearth of

havara and mudbrick to the west, and a stone-built table of offerings

on the east. It appears that during Floor I, Temple 4 underwent

significant changes in its function. Smith has argued that during Floor

III-II, this building actually served as a workshop centered on the

collection of reusable raw materials such as metal and ivory, as well as

the crafts of furniture repair or carpentry. During Floor I, the space

was re-designed, with the hearth and altar arguing for a special cult

purpose. This is further indicated by the gaming stone placed on top of

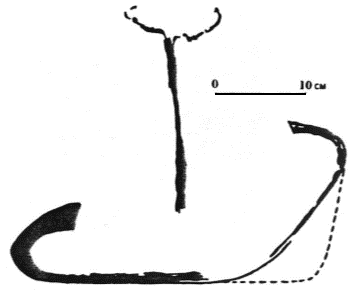

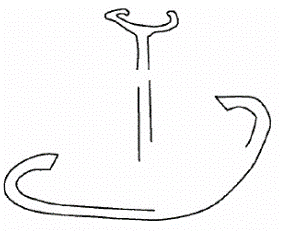

the offering table and the ship graffiti prominently placed on the

supporting side slabs.

Following the flooding of Floor I, Floor 3 (850-707) saw substantial

changes during the clean-up process, including the workshops moving out

of the area entirely or just beyond the excavation limits. By this time,

the wall at Kathari goes out of use, with a ramp over the city-wall

added between temenos B and Temple 4 providing even greater access to

the harbour. This phase initiated a rebuilding of the temples, in

particular Temple 1 on a larger scale with an enlarged outside temenos

taking over the space originally occupied by Temple 2. This enlargement

indicates the aggrandizement of the temple, not its diminished

importance. On this floor, the orthostats were furthermore covered with

gypsum, indicating a greater attention to surface detail compared to

Floor I. Smith notes that although Temple 1's architecture saw

continuity in its ashlar form and position, its "purpose and design

changed remarkably" from Floor I to Floor 3 and Floor 2A. During Floor

3, a smaller version of Temple 5 was built over its predecessor, while

Temple 2 was no longer an enclosed structure and was incorporated into

temenos B.

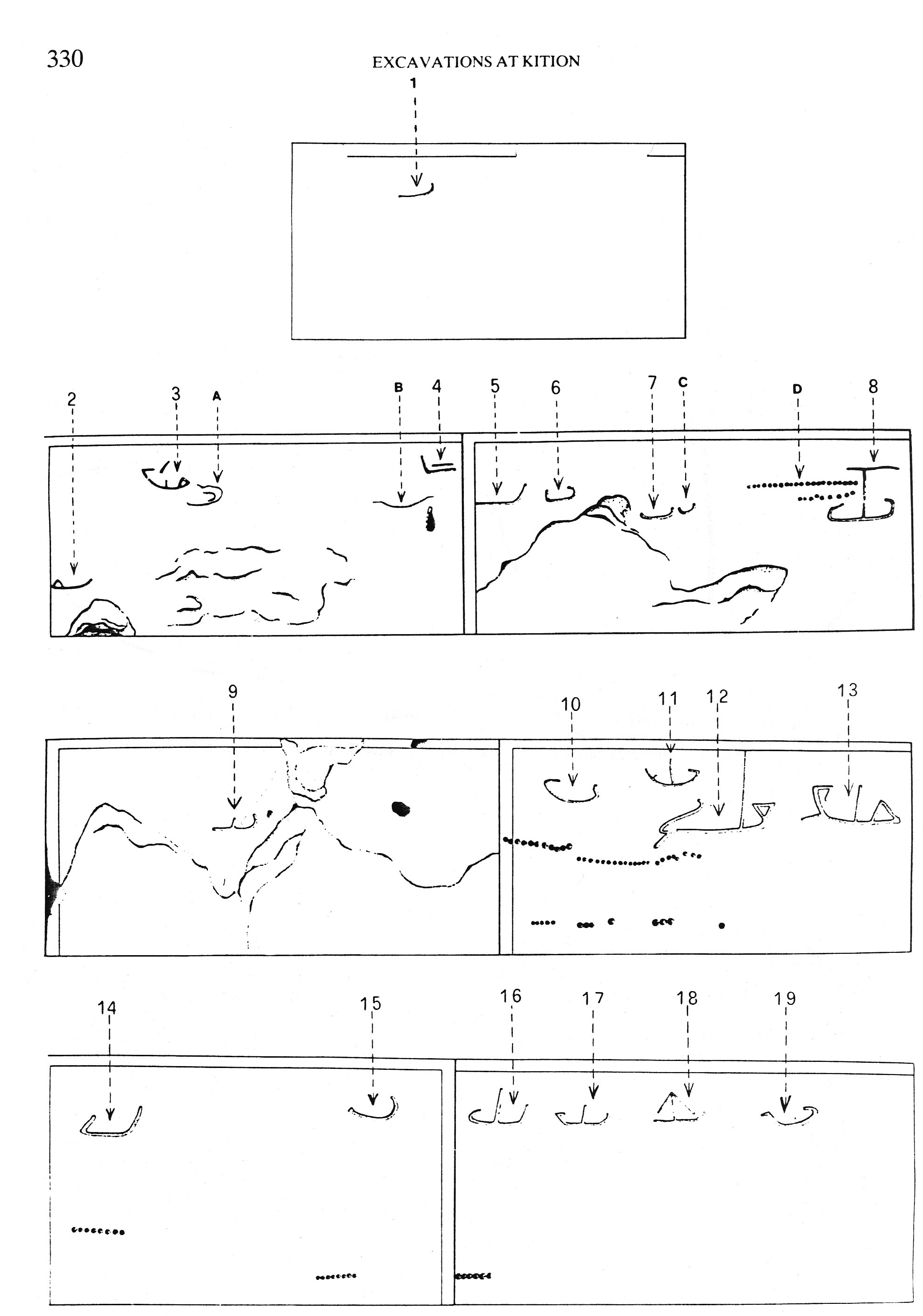

Graffiti contexts:

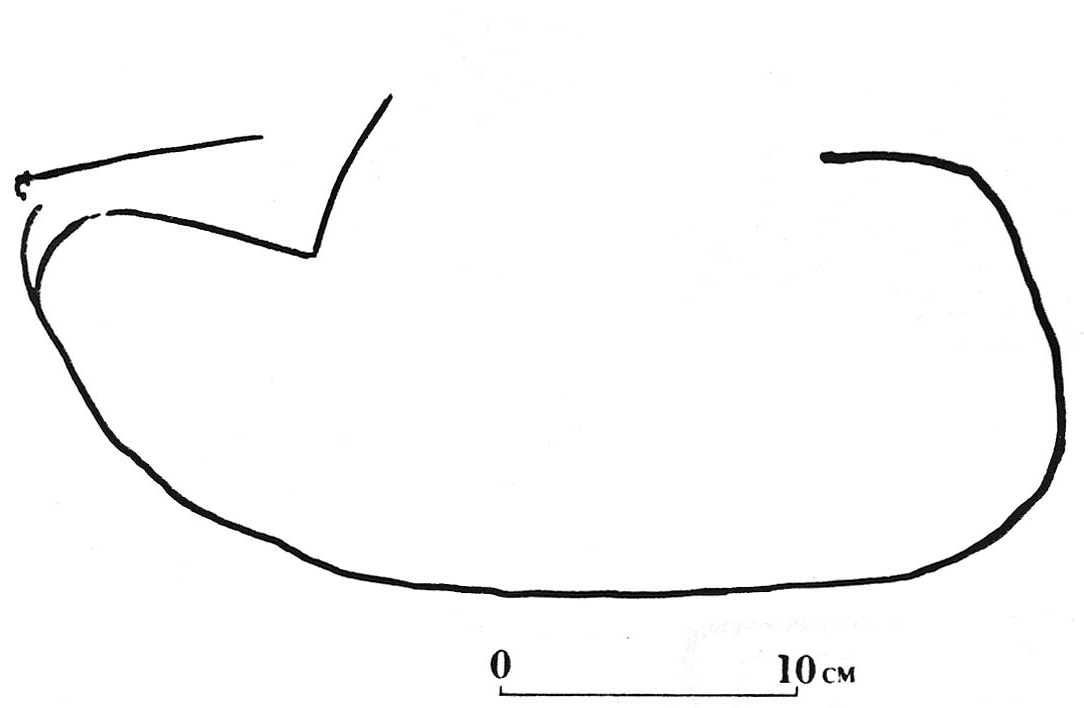

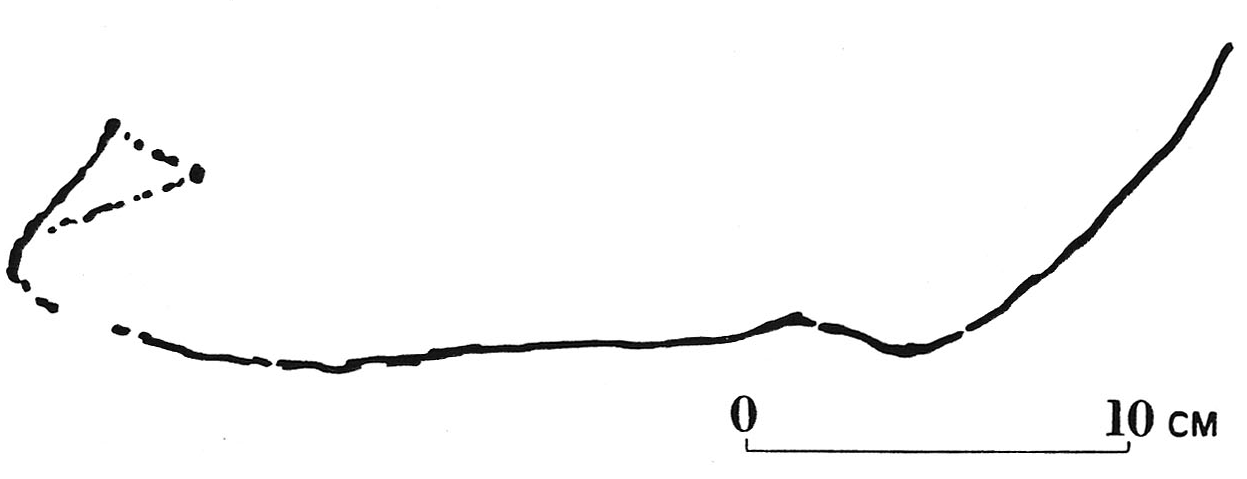

The ship graffiti are found in two clusters: 19 ships on the orthostats

of the southern wall of temple 1, and two ships (possibly a third) on

two vertical limestone slabs that compose the altar of temple 4. The

graffiti of temple 1 have a terminus post quem of c.1200 B.C. which

corresponds to the date of the wall's construction. Since the temple

complex remained in continuous use throughout the EIA, they do not have

a reliable terminus ante quem however. I disagree with Smith's

suggestion that the graffiti from temple 1 were added throughout the

entire history of use of the building from the 12th to the 6th

century. As Smith herself highlights, the purpose and design of the

complex saw remarkable changes ca. 850 and again ca. 707. This still

leaves Floor I which was in use for a considerable time. One way to

narrow down the chronological bracket is to consider the placement of

the graffiti from a visual and practical perspective. The orthostats of

the southern wall are 1.42-1.48 m high, with the ashlar footings below

them 0.35-0.5m height. The graffiti's location along the upper half of

the orthostats makes perfect sense if they were created more or less at

eye level, the most natural position for a person standing next to the

wall. This would also explain why whereas they generally cluster on that

level, there are some variations between individual graffiti, as one

would expect different individuals would vary in height. During Floor I,

the floor immediately in front of the southern wall (Courtyard C) was

raised, leaving only the upper two steps of the southeastern entrance

functional. Overall, the floor level in the temples was raised by as

much as 0.4 m, probably in response to the repeated flooding episodes.

Karageorghis notes that as a result of the higher floor level, the lower

part of the ashlar orthostats of the walls, at least for temple 2, were

no longer visible during this phase. In my opinion, this suggests that

the graffiti were most probably carved prior to the floor being raised

in court C, giving them a time range between 1200 and 1000 BC.

Given the prolonged exposure of the wall, these orthostats of temple 1

are quite weathered, with surface damage and grooves making the

interpretation of the graffiti difficult. Their fragmentary nature also

suggests that there were quite likely more ships than the 19 which were

able to be recorded. Only four of these have been documented in greater

detail. The different techniques of engraving suggest that the graffiti

of temple 1 were executed by multiple hands. The suggestion that the

orthostats and graffiti were re-used from a previous context as

suggested by Le Bon should be rejected (Le Bon 1997: 90). The main reason is that

the use of ashlar masonry is a distinctive feature of the early 12th

century construction. More specifically, the orthostats on which the

graffiti are found are made of a reef limestone obtained from the

Koronia formation some 20 km away by sea, specifically selected for its

visually-striking whitish-color. Their procurement was thus clearly part

of the large-scale LC IIIA project. Finally, in the original report

drawing ship 5 was depicted as if it was only partially preserved at the

edge of an ashlar block, giving the impression that the orthostats had

therefore been re-used. A closer re-examination by Artzy and Basch

however revealed that the graffito was in fact complete, thus dispelling

this concern (Artzy and Basch 1984: 325).

The altar of temple 4 was constructed for floor I (1000-850). The table

of offering was enclosed on four sides by single or double row of

vertically placed slabs. These cut through Floor II, with more than half

of the preserved height of the table lying below the level of Floor I.

The resulting height above the floor level was only 0.4-0.5 m. The ship

graffiti are located on slabs 4 and 5 and were only just visible above

the level of the floor, which gave them an appearance of floating at

sea. While the table of offerings remained visible in later periods, the

vertical stone slabs were only visible for this floor. The re-dating of

the floor however no longer gives a short chronological bracket for the

graffiti. There is no question that attention was given to the graffiti,

which were placed on a conspicuous location on the sides of the altar.

The presence of the gaming stone forming part of the surface of the

offering table might suggest some form of cult related to divination.

Smith notes that during Floor I, the main room may not have been roofed,

with the smoke rising probably visible from the harbour. Since the

gaming stone was itself potentially re-used, it is quite possible that

the slabs, including the ones bearing the ship graffiti were also in

their secondary use for the altar although they clearly continued to

have significance during this phase. I would argue that the creation of

the graffiti from temple 1 and 4 should be placed prior to Floor I. This

is based on the practical considerations outlined above, as well as the

fact that all other known graffiti cluster strictly within the last

phases of the LBA. Besides a similar cultic function, the typological

similarities between the Kition graffiti and the ones from Akko are very

hard to ignore. Furthermore, unlike Amathus and Salamis, Kition has

provided no ship imagery dating to the later parts of the EIA with the

exception of a single boat model. Taken together, it is thus quite

unlikely that the graffiti should be dated after ca. 1000 BC.