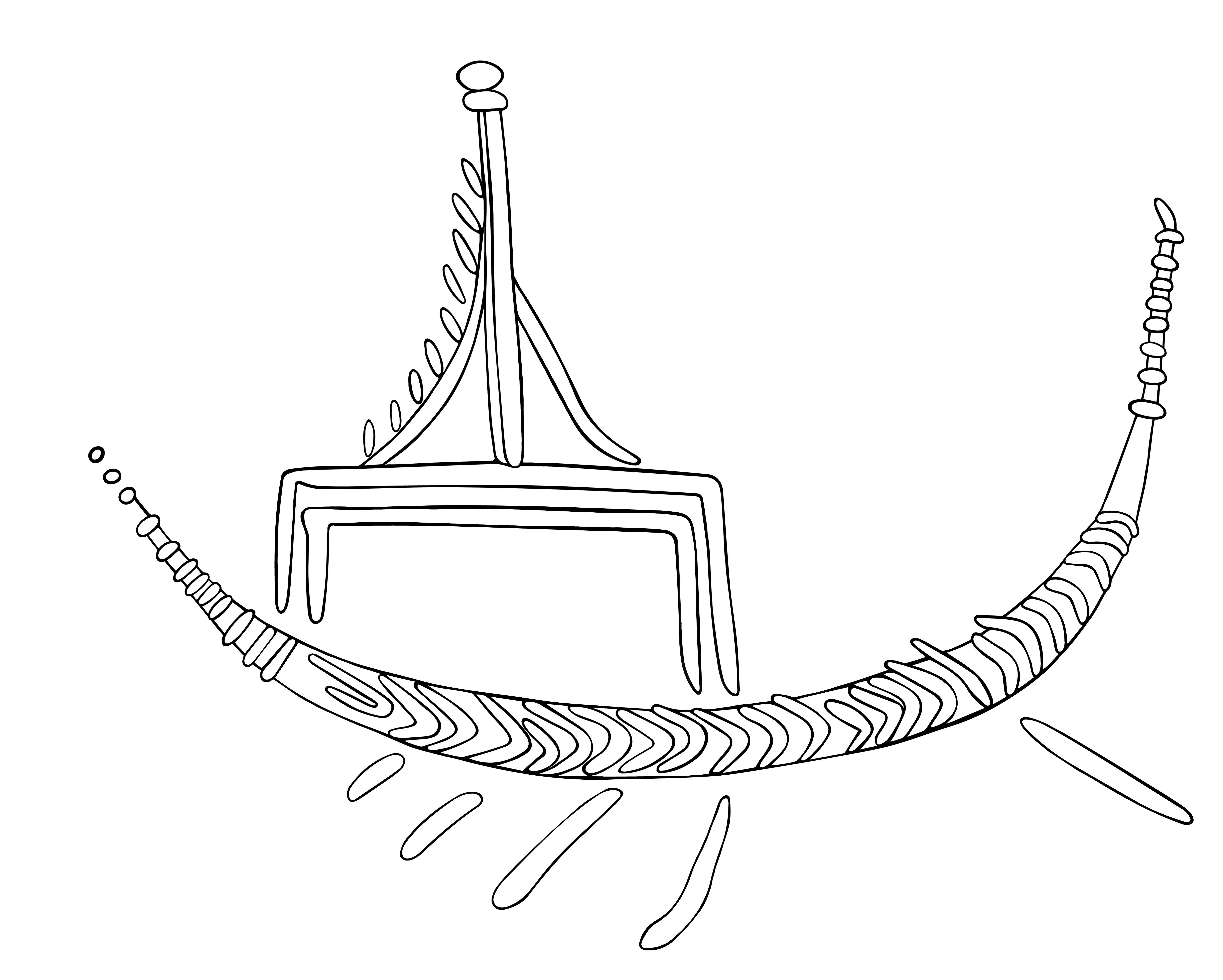

Ship to the left with a crescentic hull ending in pointed extremities. The stern is slightly higher than the bow. On the for'ard section of the hull there is a rectangular construction (awning) with a mast supported by two stays rising out of it. The oblong globules on the for'ard edge of the mast and stay are probably dress lines. Steering oar and three oars pointing for'ard.

Maritime ceremony

A39

Ring: LH II (on stylistic grounds); context: LH IIIC

Tiryns treasure, southern part of the Tiryns lower town, immediate vicinity of "Megaron W"

bezel L: 3.4 cm; B: 1.95 cm; hoop diam.: 1.9 cm

Gold signet ring, gold plate over lead core. Elliptical shape

Delivorrias 1987: 146, nr 38; CMS I, Kat.Nr. 180; Evans 1928: 245-246; Karo 1916: 143-147; 1930: 122-124, pl. XXX.1; Köster 1923: no. 14; Nilsson 1950: 38-39; Paule 2016: 47-48, figs. 3.6a-b; Philadelpheus 1916: 15-17; Tartaron 2013: 54-55, fig. 3.7; Tzahou-Alexandri and Spathari 1987: 78, nr 35; Wachsmann 1998: 99, fig. 6.28; Wedde 2000: 340, no. 911

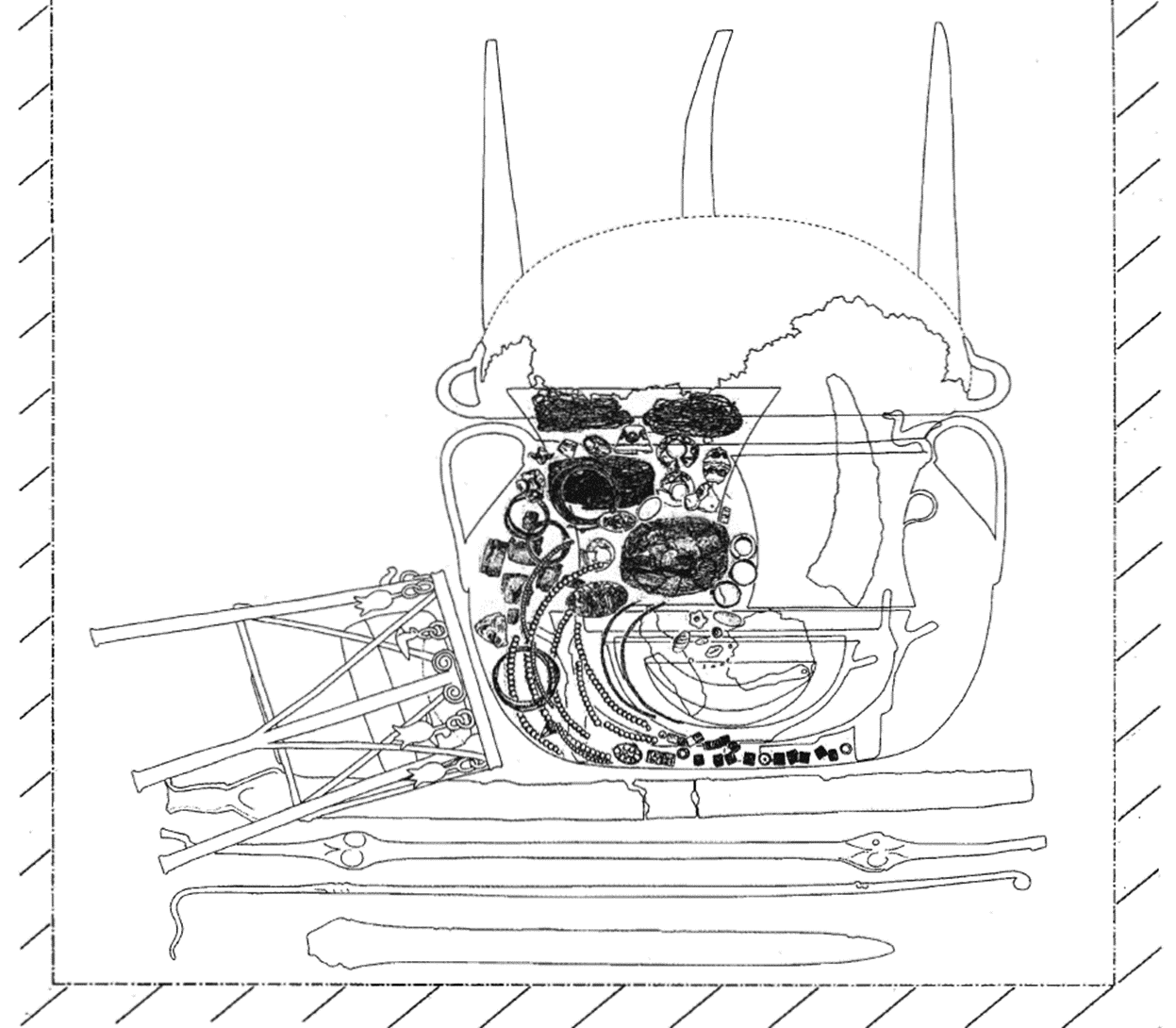

Context: The Tiryns treasure has been interpreted by Maran as the keimelia of a prominent post-palatial family, suggesting an attempt by post-palatial elites to secure legitimacy by appropriating and displaying political symbols of the preceding post-palatial period (Maran 2006; 2012). The objects contained within vary in date, ranging from the early Mycenaean period to LH IIIC when the hoard was deposited. The treasure was not a miscellaneous collection of arbitrarily piled up valuables, but instead follows a certain logic according to carefully selected patterns. Its contents can be classed under two main categories: 1) jewellery, and 2) a set of bronze ceremonial feasting equipment comprised of open shapes (bowls, basins, mug, chalice) and utensils for preparation and serving (cauldron, tripod stand, fire-dogs). The bottom of the treasure pit was first paved with small flat stones, after which two damaged swords and the pair of fire-dogs were deposited. A large bronze cauldron with an upside-down tripod serving as a lid was then placed on top of these, while a Cypriot bronze tripod stand and a bronze ingot were leaned against it. The cauldron was then filled with seven bronze vessels, two knives (bronze, iron), jewellery (gold, semi-precious stones, amber and faience), and pieces of worked and unworked ivory. A distinction was furthermore drawn between raw and scrap bronze metal which remained outside the cauldron, and valuable raw materials and finished objects which were deposited inside it. A39 is one of two gold signet-rings which are arguably the most obvious items linked to symbols of authority of the palatial period.

Scene: From left to right as seen on the ring: A woman and a man stand in a door frame, the woman’s right hand seemingly tugging at the man’s arm which is extended towards her face. To their right is another man/woman pair, facing each other with one arm raised. On the right side of the composition, a ship with four people, two of which are sitting under an awning structure amidships facing each other. The helmsman is showed standing facing towards the sea, while a fourth male figure, depicted on a larger scale, looks in the other direction towards the shore. A squid is depicted near the steering oar.

The crescent-shaped lines along the hull are seen by Wedde as an indication that this is a papyrus craft.

Delivorrias, A. (ed.) 1987. Greece and the Sea. Catalogue of the exhibition organized by: the Greek Ministry of Culture, the Benaki Museum, the National Foundation De Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam, in honour of Amsterdam Cultural Capital of Europe 1987. Athens.

Evans, A. J. 1928. The Palace of Minos. Vol II. London: Macmillan.

Karo, G. 1916. “Archäologische Funde im Jahre 1915. Griechenland,” AA: 138-166.

―――. 1930. “Schatz von Tiryns,” AM 55: 119-140.

Köster, A. 1923. Das antike Seewesen. Berlin: Schoetz & Parr-hysius.

Nilsson, M. P. 1950. The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and its Survival in Greek Religion. 2nd edit. Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup.

Paule, A. 2016. “The Development of Protohistoric Jewellery from Cyprus and the Aegean: An Analysis with Special Reference to Signs of Cultural Interconnections,” in R. Maguire and J. Chick (eds.) Approaching Cyprus. Proceedings of the Post-Graduate Conference of Cypriot Archaeology (PoCA) held at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, 1st-3rd November 2013. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 40-59.

Philadelpheus, A. 1916. “Ζʹ Αρχαιολογικὴ Περιφέρεια. Ό μυκηναϊκòς θησαυρòς Τιρύνθος,” AD 2: 13-21.

Sakellariou, A. 1964. Corpus der minoischen und mykenischen Siegel. Band I. Die minoischen und mykenischen Siegel des Nationalmuseums in Athen. Berlin: Gebrüder Mann.

Tartaron, T. F. 2013. Maritime Networks in the Mycenaean World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tzahou-Alexandri, O. and Spathari, E. 1987. A Voyage into Time and Legend aboard the Kyrenia Ship. Athens: Ministry of Culture.

Wachsmann, S. 1998. Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

Wedde, M. 2000. Towards a Hermeneutics of Aegean Bronze Age Ship Imagery. Peleus Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Griechenlands und Zyperns, vol. 6. Bibliopolis: Mannheim and Möhnsee.