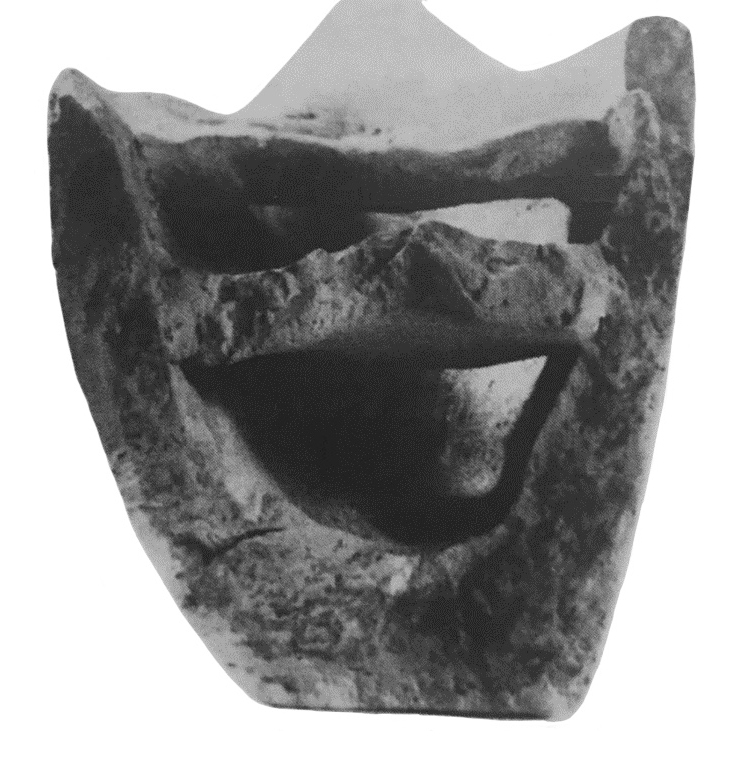

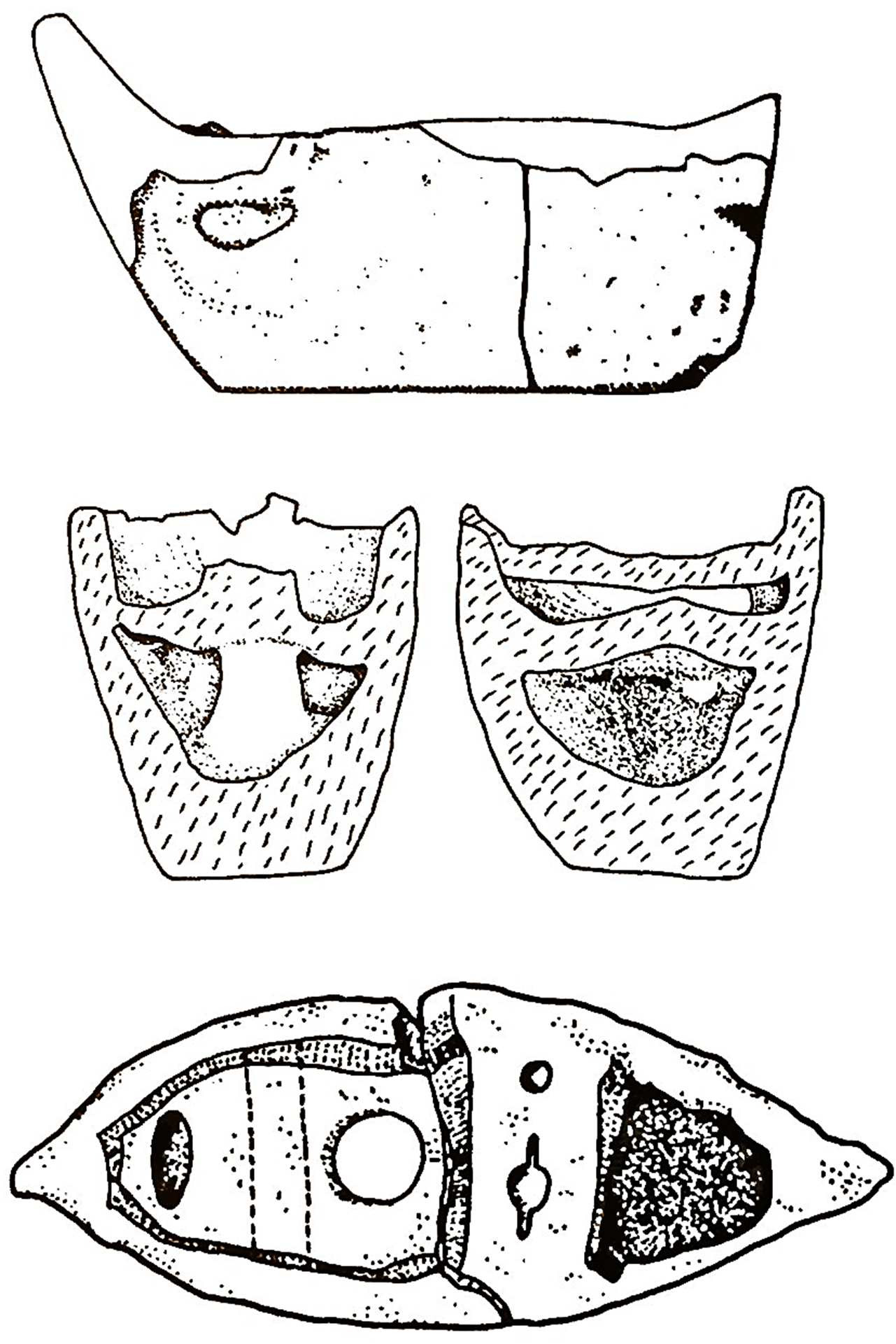

Pointed bow and stern, with the right extremity being nearly vertical while the left one curves at a steep angle (restored as a raised bow). The mast amidships is indicated by a step. Deck inside the hull at mid-height which does not run its full length. It runs from just aft of the bow to just forward of the stern and side to side below the two thwarts. There are two thwarts above the deck. The aftmost thwart originally had two objects attached to it.

Ship model

A36

LM IIIC (1200/1190-1075/50) or 8th-7th century

Agia Triada, Piazzale dei Sacelli (sanctuary)

L: 21.5 cm; W: 8 cm; H: 8.5 cm (ratio: 1:2.7)

teracotta model, whitish clay with traces of red paint

Herakleion Archaeological Museum 3141

D'Agata 1999: 158, pl. XCVIII; Gray 1974: 18, nr. 32; Johnston 1985: 25, BA 15; Laviosa 1969-70: 27-28, fig. 27a-d; Marinatos 1933: 174, nr. 23, pl. 14.23; Wedde 2000: 308, no. 301; Wachsmann 1998: 104-105, fig. 6.37

D'Agata's study of the votives (terracotta and bronze statuettes) has identified three chronological phases in the cult of the sanctuary: LM IIIC-SM, PG-Orientalizing, and Hellenistic (D'Agata 1999). Piazzale dei Sacelli was an open air shrine established in LM IIIC in the most important area of the BA site, which from LM I had been "the traditional centre of social, political and religious power in the settlement." (D'Agata 2000: 351). Henceforth the area was reserved exclusively for cultic use. The earliest phase (12th-11th centuries) is characterized by three types of wheel-made offerings: bulls, fantastic animals, and horns of consecration. These are elaborately made and typically adorned with complex painted decoration which point to features that have been assigned to various regional and chronological traditions (LM, LH, Aegean), indicating the composite milieu of the sanctuary. The cult of this phase has been interpreted as an expression of territorial control by the new ruling elite of Phaistos, incorporating into its iconography Minoan symbols (horns of consecration), new types of cult objects (fantastical animals with human heads and legs), and Mycenaean elements associated with warrior iconography. The LH IIIC phase has also provided two fragmentary oxhide copper ingots (a half and a quarter), which were analysed and shown to have a lead isotope composition matching that of ores from Apliki on Cyprus (Lo Schiavo et al 2013). Given their ritual deposition, these might indicate a showcasing by the local elites of their monopoly on the supply of raw materials (D'Agata 1999: 218, n. 606, 234). It has been argued that both the fragmentary ingots and the terracotta votives indicate a particular connection with dedicatory practices in Cyprus (Ibid.: 73-75).

D'Agata argues that there was a break between the first two phases of the sanctuary. The votive offerings dating to the second phase (9th to the beginning of the 7th century) are interpreted to mark a radical transformation compared to the preceding phase, with handmade human figurines and bronze bulls being most common. Although far fewer in number, diverse votives are also attested: "wheel-made human figures; bronze human figurines; clay animals; bronze and wheels; and clay objects and vases, among them model of ship, askoi, lids probably used as votive shields, kernoi and at least one pithos decorated with plastic animal." (D'Agata 1998: 23). During this phase the sacred area was expanded, as offerings were no longer limited to the paved esplanade of the piazzale but were also deposited in the proximity of a Minoan building which was still visible - suggesting a relationship to the past and its remains. The second phase of the sanctuary corresponds in date to the settlement to the west of the palace of Phaistos and was probably related to it.

Dating: D'Agata prefers to date the model to the EIA phase of the sanctuary (8th-7th century), noting that Aegean ship models of the LBA don't usually show that amount of detail, and that models are more prevalent in the Archaic period. Unfortunately, the offerings deposited in the open-air area which accumulated over time have no micro-contexts, so that all votives have been dated stylistically. This isn't very helpful in the case of the boat model because both in the LBA and EIA periods, the medium shows very little uniformity. Since there are no good morphological parallels and there is no painted decoration to provide additional clues, a stylistic dating is unreliable in this particular case. The fact that the post extremities of this model no longer survive further problematizes this issue.

The restoration is arbitrary, the model does not preserve either post extremity, and so the identification of the bow/stern is uncertain. This model provides incontrovertible evidence for a deck. The thwarts indicate that the deck is below the level of the rowers, which means it was not necessary to restrict its extension because of a need to seat the crew on the same crossbeams that the planking would rest on. In general, the later development of the deck tended towards laying it above the rowers (at shoulder height or above their heads) in order to create a fighting platform or a protection for the goods in the hold. A slight protrusion on one of the thwarts may originally have been part of a steering mechanism. Wedde thinks that it is uncertain whether the model represents a large or a small vessel but favours a larger vessel because of the presence of a deck below the thwarts which possibly suggests a cargo carrier of some size. The model has proportionately high sides, unless this ratio has been exaggerated because of the artist's attempt to accommodate both the deck and the thwarts. This would support the correlation between a shallow hull and absence of deck vs a deep hull and presence of deck.

D’Agata, A. L. 1999. Hagia Triada II. Statuine minoiche e post-minoiche dai vecchi scavi di Hagia Triada (Creta). (Monografie Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Atene 11). Padova: Bottega d’Erasmo.

Gray, D. 1974, Seewesen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

Johnston, P. F. 1985. Ships and Boat Models in Ancient Greece. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Laviosa, C. 1969-70. “La marina micenea,” Annuario 47-48: 7-40.

Marinatos, S. 1933. “La marine créto-mycénienne,” BCH 57: 170-235.

Wachsmann, S. 1998. Seagoing Ships & Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

Wedde, M. 2000. Towards a Hermeneutics of Aegean Bronze Age Ship Imagery. Peleus Studien zur Archäologie und Geschichte Griechenlands und Zyperns, vol. 6. Bibliopolis: Mannheim and Möhnsee.