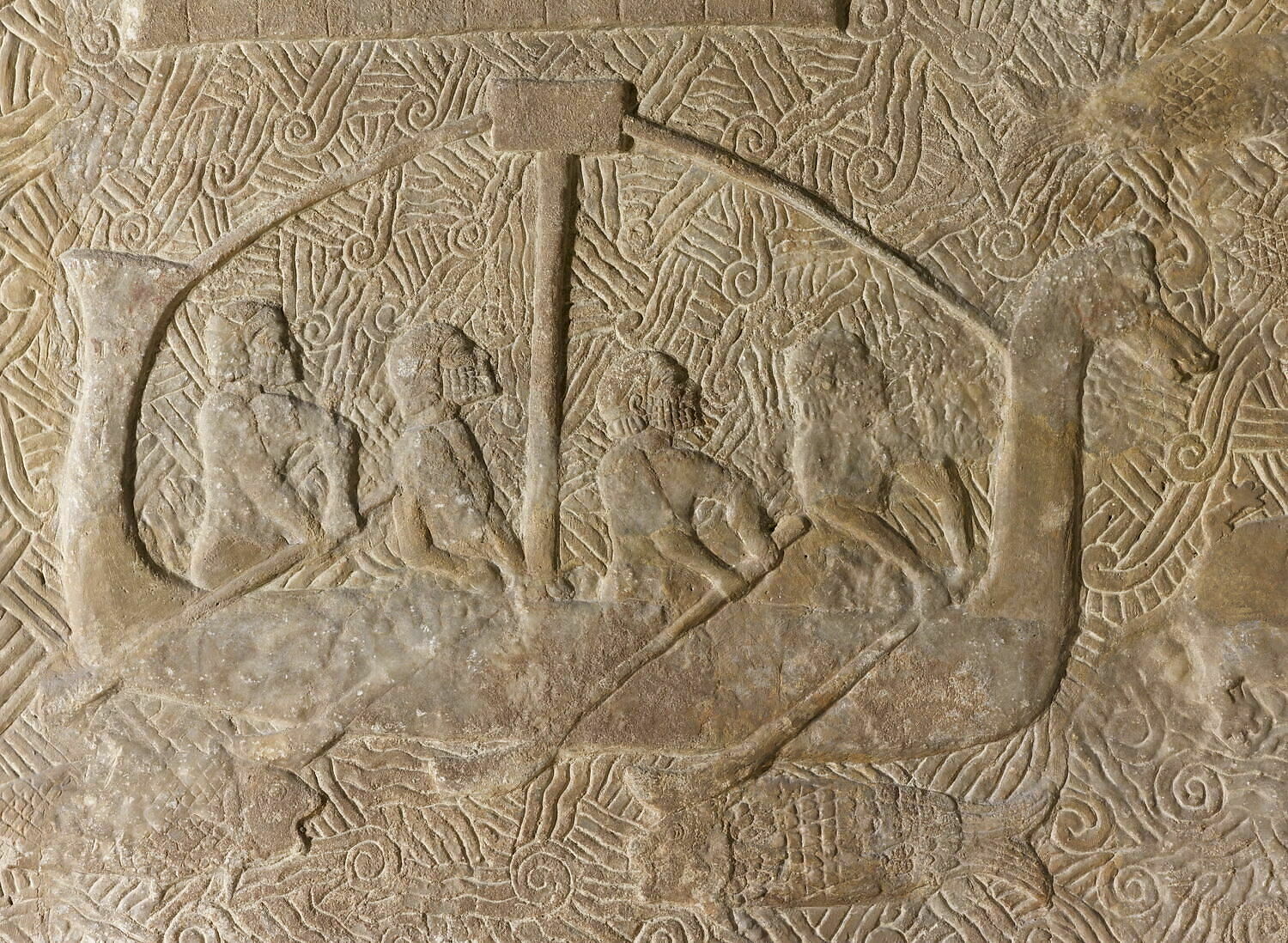

Sixteen vessels of identical hull design,

with a flat hull and high symmetrical vertical posts. The stempost ends

in a naturalistic horse headed device. The sternpost has two possible

variations. The first one - observable on only two ships - tapers with

a slight outward curve into a pointed tip. Both vessels are located on

the double slab AO 19889, to the right of each fortified island. The

second and most common sternpost device is vertical and flares out into

a shape that resembles an inverted triangle, capped by a straight

horizontal edge. This form is identical to the rounded Phoenician ship

type represented on the Kuyundjik relief, as well as the

Syro-Palestinian merchant vessels of the LBA.

Three of the ships are

furthermore depicted with a mast amidships and two stays, fore and aft.

All of them are empty and face right, on their way to fetch a new charge

of timber. Two of them have a rectangular device at the top of their

mast which must be a mast cap. This is strengthened by a comparison with

the third ship, which has a different shape capping the mast that

resembles a sort of basket or bell shaped device which identifies it as

a crow's nest. The absence of the mast in cases where the ships are

loaded indicate that they were unstepped for this purpose.

In the

majority of cases the ships are manned by four figures, operating oars

with rounded oar blades. If a riverine context is considered, then these

could be paddles used to steer or regulate the direction of the boats

when floating down the rivers' currents, and alternatively as punting

poles when towed upriver.

Timber transport by boat

L29

c. 716-713 B.C.

Palace of Sargon II (Court VI), Dur-Šarruken, Iraq

AO 19891: H: 3.08 m; 2.41 m; AO 19889: H: 3.08 m; L: 4.09 m; AO 19890: H: 3.08 m; L: 2.41 m; AO 19888: H: 3.03 m; L: 2.16 m

Five carved slabs of gypseous alabaster (also known as Mosul marble) in severely damaged and partly reconstructed condition

Aruz et al 2014: xvi-xvii; Basch 1987: 306-309, no. 650, 651; Parpola 1995: 74, n. 78; Parrot 1950: 115-117; Thomason 2001: 69, fig. 2; Vigneau 1935: 11, pl. 4; Detailed studies: Albenda 1983; Fontan 2001; Linder 1986; Trakadas 1999: 58-71, figs. 20-25

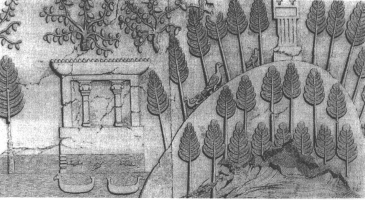

Dur-Šarruken ("Sargon's Fortress") was an entirely new city built on virgin soil - a gigantic construction project that was meant to be the king's crowning achievement. This allowed for a perfectly symmetrical ground plan with no concern for the surrounding landscape, with the palace, temples, and arsenal placed on two enormous platforms that was constructed from scratch. The composition depicts the various stages in the transport of lumber, starting with the hauling of the felled timbers at the foot of a mountain, their shipping, unloading, and delivery. Originally consisting of seven slabs, only five are extant, with panels 5 and 6 now lost. The felling itself is omitted: "the artist's attention is focused on the process and techniques of the loading, transporting and disposing of the lumber."(Linder 1986: 273). The importance placed on the scene is indicated not only by the great detail in which the process is portrayed, but also its privileged placement on one of the facades of the main courtyard of the palace which preceded the throne room. Sargon is represented on each side of the monumental gate leading to the north quarter of the palace, facing delegations marching towards him. This file continues in the corridor 10 leading to other reception rooms. All of the subjugated nations are represented, symbolizing his domination over the known universe.

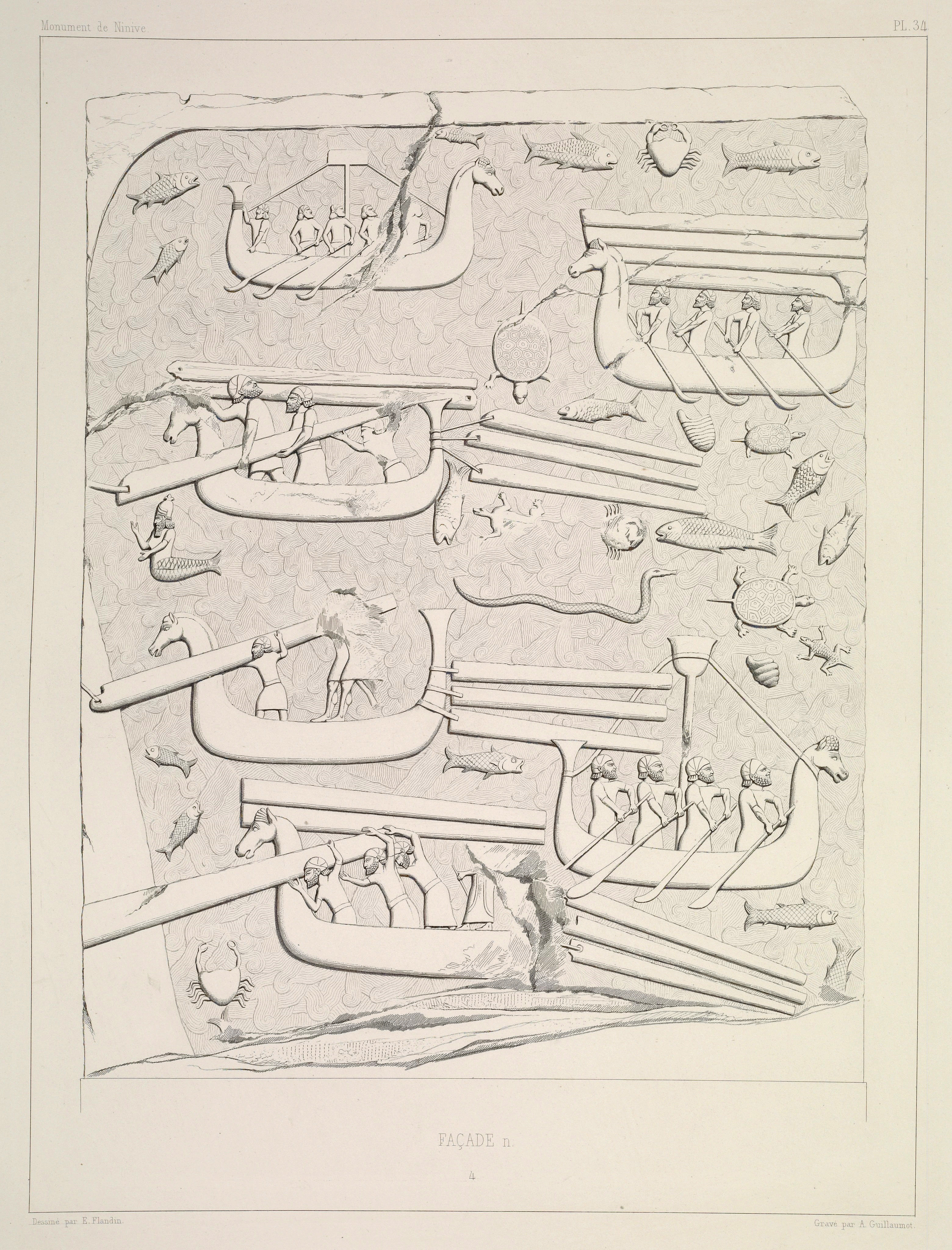

Gypseous alabaster or Mosul marble was the material of choice used by the Assyrians to make orthostats. The frieze comprising five panels was meant to be read from right to left. The exact extent and order of the original composition is uncertain, as all of the panels except of the first one to the left were found crumbled. The drawings made by Flandin reveal that there was an additional panel to the right showing a navigation scene of which no fragments survive. Due to the lack of inscriptions describing the scene, the panels have been subject to numerous interpretations in terms of the source of the timber and the setting. These range from the Phoenician coast, Cyprus, the Zagros mountains and the Amanus mountain range. Parpola and Linder in particular have rejected the Mediterranean coast as a setting altogether, arguing for a riverine operation instead.

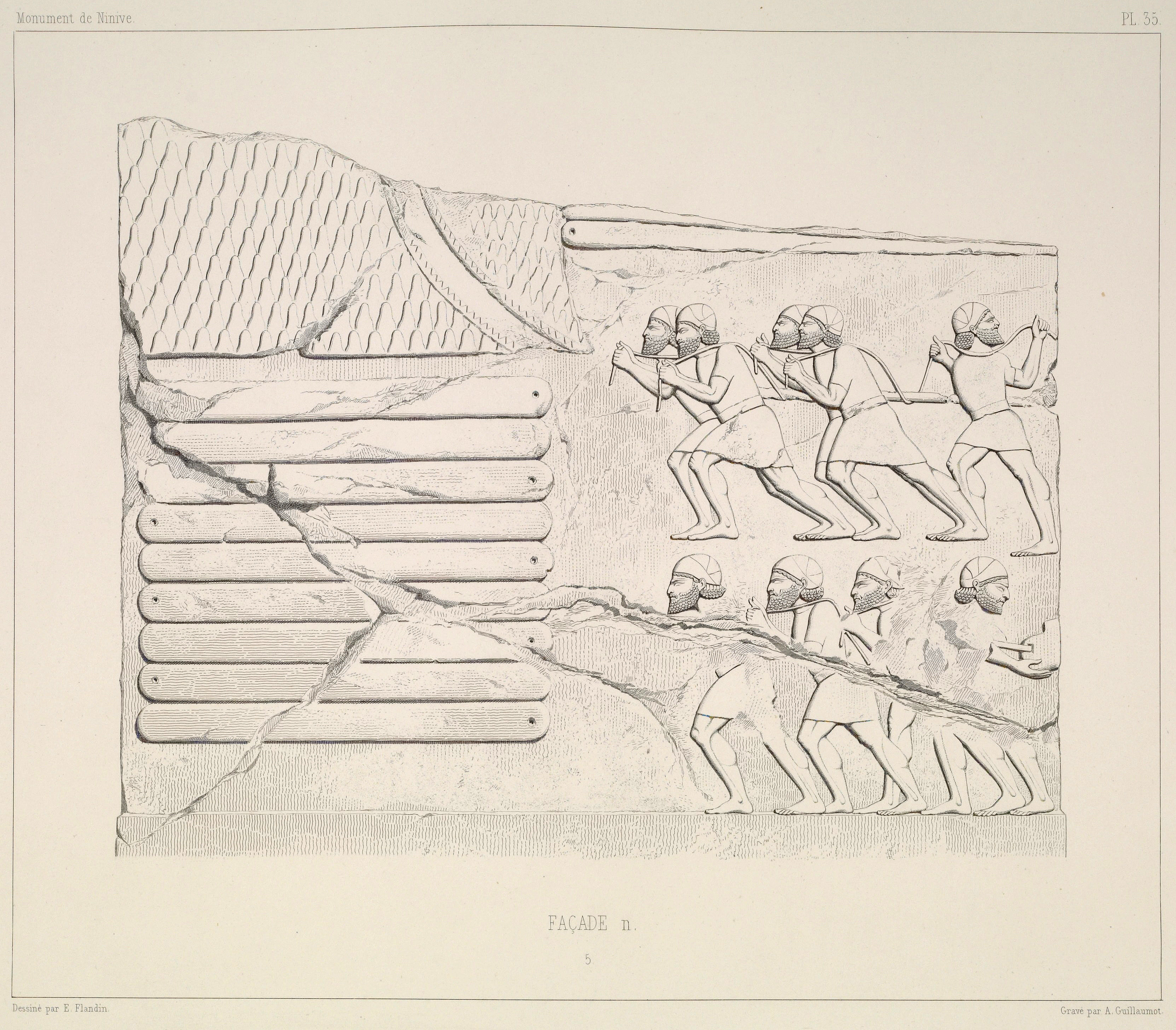

1. AO 19891: Timber being unloaded. Lower part of a slab with the upper part being a modern restoration. Eleven figures arranged in three registers are hauling a charge using a rope. All of the men are depicted in the same manner, with short curly hair, a short pointed beard and the characteristic cap resembling a sort of turban. The end of a beam is observable at the bottom. At the foot of a densely forested hill with a road leading to the summit is a pile of nine logs, trimmed and bored to accommodate a rope. To the right is another pile of five logs. The wooden beams are symmetrically shaped, with rounded ends that indicate they have been already treated by carpenters prior to shipment.

2. AO 19889: Two slabs joined together. Ten boats with a horse-headed device decorating the bow are sailing over the Mediterranean Sea teeming with marine life (fish, turtles, crabs, sea snake or eel) and fantastical creatures serving as protectors (merman, two winged bulls). There are also non aquatic forms observable, such as a lizards and a scorpion. Eight ships are sailing to the left, heavily loaded with 3-4 logs and towing 2-3 additional logs behind them. A dual system of transport is therefore depicted, with logs carried dry on board and others towed behind the boats in the water, joined by rope though holes at their front ends. Two empty ships are sailing in the opposite direction, presumably on their way to fetch logs. Each ship is manned by 3-4 crewmembers. Two small islands are depicted amidst the mass of ships and sea creatures. Both have fortresses but are distinguished by the fact that the right one is a natural rocky outcrop, while the left one rests on a constructed foundation. The island cities have been typically identified as Tyre and Arwad respectively, but Parpola, Linder, and Trakadas have rejected the maritime nature of the landscape altogether, opting for a riverine setting.

3. AO 19890: Six ships, four of which are nearing the shore while two are pulling away in the opposite direction. The vessels are manned by 3-5 crewmembers. Three of the ships that have approached the shore are shown in the process of unloading a log. The scene is decorated with sea creatures and a merman as on the previous panels.

4. AO 19888: Twenty eight figures are busy unloading timber in a mountainous landscape. A pile of ten logs has been reconstructed.

The composition is fraught with interpretative problems

since there is no accompanying inscription to identify the location or

the actors. If a maritime setting is rejected in favour of a riverine

one as some have proposed, the identification of the ships becomes less

certain. The reading of the scene as a representation of the Levantine

coast can no longer be taken for granted as it has been in much of the

previous literature.

The liberties that the artist has taken, such as

the impossible manner in which the logs are shown being carried aboard

the ships, further problematizes any attempt at a close technical

reading. These logs are depicted in piles of 3-4 as if floating above

the hull and crew, with the lowest one at the level of the stem and

sternpost extremities - an impossible position way above the boat's

balance point. While unrealistic, this flattened depiction style is

typical for Assyrian artistic convention and makes perfect sense given

that the timber itself is the showcase of the panels. Priority was thus

given in displaying the cargo clearly, in this case quite literally

outside the ships.

The extant Assyrian administrative texts dating to

Sargon II's reign do not mention Lebanese timber, but instead repeatedly

document the procurement of timber from the Zagros, Taurus and Amanus

mountains which were much closer to Khorsabad, thus providing a much

easier supply via river-borne transport. The towing of the logs behind

the boats furthermore would have been very dangerous outside a riverine

environment. In the Old Testament, the timber obtained by Solomon from

king Hiram I of Tyre was sent down held together in rafts, not by boat.

This in no way precludes however, that Phoenicians were enlisted given

their long-established expertise in the procurement and transport of

timber, including for another earlier grand building project, namely

Solomon's temple. The conscription of vassals for labor was furthermore

not uncommon for Assyrian rulers. Already during Ashurnasirpal II's

reign (883-859 B.C.) we hear of deported Tyrians and Sidonians to

Mesopotamia as forced labor for the construction of his palace at

Nimrud. The plausibility of this interpretation is further strengthened

by the fact that the crewmembers of the ships are clearly foreigners.

The specific headgear (leather caps) they wear is typically identified

with Syrians and other western vassals. It is therefore likely that

Phoenicians were enlisted to both craft and operate the boats.

Albenda, P. 1983. “A Mediterranean Seascape from Khorsabad,” Assur 3.3: 1-17.

Aruz, J., S.B. Graff and Y. Rakic (eds.). 2014. Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Basch, L. 1987. Le musée imaginaire de la marine antique. Athens: Institut Hellénique pour la preservation de la tradition nautique.

Fontan, E. 2001. “La Frise du Transport du Bois, Décor du Palais de Sargon II à Khorsabad,” AHL 14: 58-63.

Linder, E. 1986. “The Khorsabad Wall Relief: A Mediterranean Seascape or River Transport of Timbers?” JAOS 106.2: 273-281.

Parpola, S. 1995. “The construction of Dur-Sarrukin in the Assyrian Royal Correspondence,” in A. Caubet (ed.) Khorsabad, le palais du roi Sargon II d’Assyrie. Paris: Documentation Française, pp. 47-77.

Parrot, A. 1950. “La scène maritime de Khorsabad,” Sumer 6: 115-117.

Thomason, A. K. 2001. “Representations of the North Syrian Landscape in Neo-Assyrian Art,” BASOR 323: 63-96.

Trakadas, A. L. 1999. “Skills as Tribute: Phoenician Sailors and Shipwrights in the Service of Neo-Assyria.” MA dissertation, Texas A&M University, US.

Vigneau, A. 1935. Encyclopédie photographique de l'art. Paris: Tel.