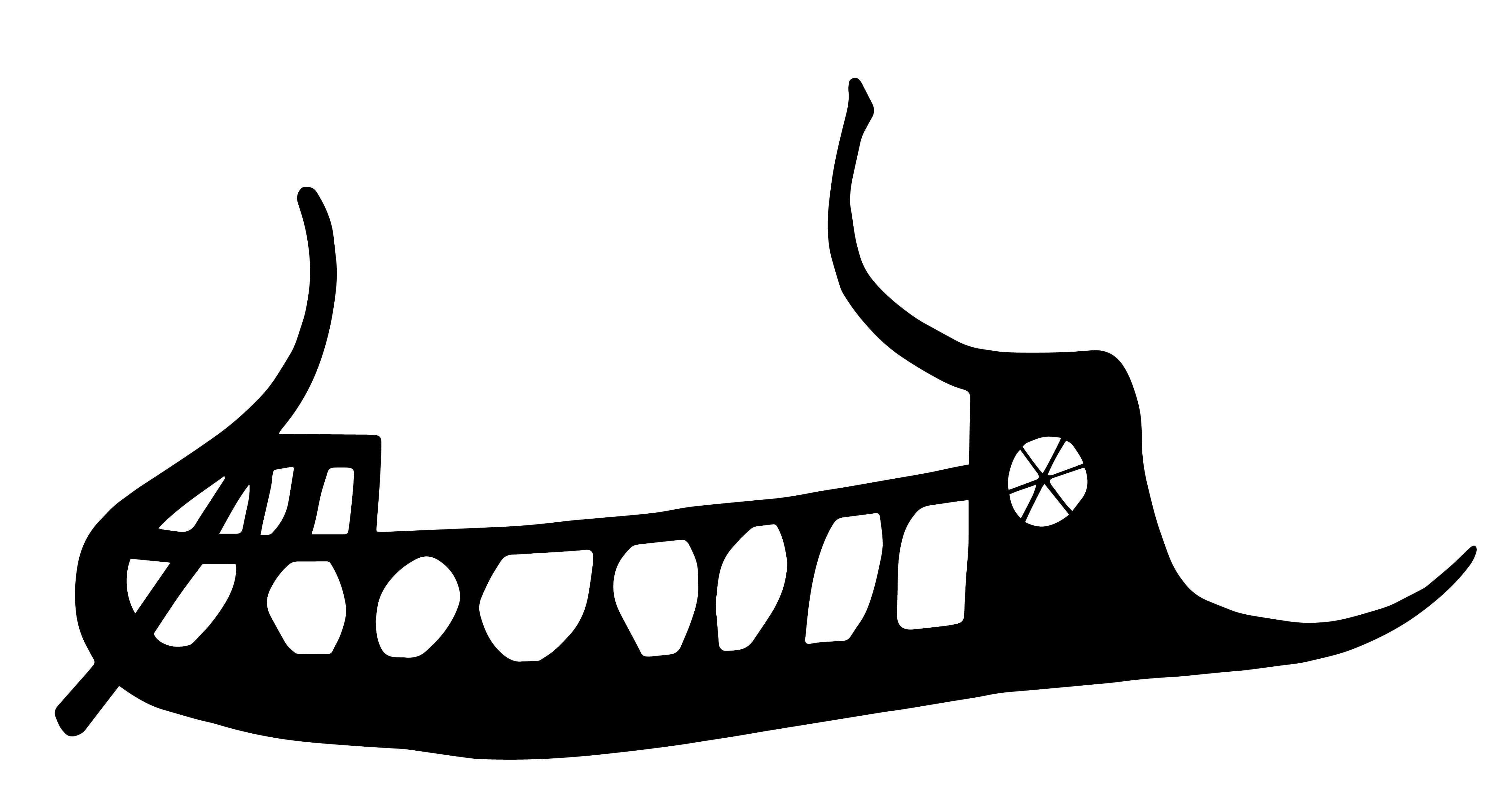

Single-levelled capsized ship to the right. Slightly rockered keelline, massive square bow with a concave stempost integrating the bow projection and a six-spoked eye. The stem- and stempost terminate in similar horns that slope inward then upward, with the stempost being slightly higher. The stempost begins to curve early, at the level of the eye, and terminates in a slightly curving bow projection. Curving sternpost with aftercastle and a quarter rudder. The aftercastle is drawn as a rectangle subdivided by two vertical lines, suggesting an open balustrade with a railing. The hull has eight approximately circular portholes, with the quarter rudder shown crossing the portholes at the stern. The gunwale planking projects slightly from the stern.

Capsized ship

A170

Late Geometric II (c. 720 B.C.)

Attica

H: 21.5 cm

Attic oenochoe

Munich 8696 (Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek München)

Basch 1978: 175, no. 370; Bennett et al 2002: 25-26, fig. 7; Coldstream 2003: 336, fig. 112c; Fittschen 1969: 49; Hall 2002: 232; Gunter 2016: 218, fig. 3; Hurwit 2011: 1-4, figs. 1-3 (narrative); Kannicht 1982: 75; Lindenlauf 2004: 421, pl. 2; Morrison-Williams 1968: 35, Geom. 38, pl. 7a; Osborne 1998: 35-37, ill. 14

Neck panel showing a shipwreck scene with a capsized ship to the right. There are eleven figures, ten of which are floating around the ship, seemingly clinging either to one another or to the ship itself. One figure differs in that it is upright, apparently sitting astride the keel of the upturned vessel, his legs seen dangling through one of the oval portholes. The figures wear crested helmets and corselets indicated by a cross-hatched motif on their torsos. Eleven fish of slightly varying sizes swim below, above and besides them. One of the smaller fish appears to be nibbling at the torso of the figure touching the stern's horn.

The scholarly debate oscillates between interpreting the depiction as a mythological scene showing the shipwreck of Odysseus versus rejecting a distinct narrative altogether. The latest and most detailed narrative discussion by Hurwit highlights that the image is purposefully ambiguous, blurring the distinction between heroic myth and aristocratic life, thus inviting the viewer to supply his own concrete interpretation. There is, however, one unambiguous point which stands out in terms of the composition of the vase: the upright figure sitting astride the keel is placed at the exact midpoint of both the scene and the vase, precisely below the vessel's spout. The axial and vertical position was thus clearly intentional and meant to highlight this individual as the main figure, who alone had a different fate from the remaining haphazardly drowning figures. The remaining men have been interpreted as trying to hold on either to their companions of parts of the wrecked ship. If correct, the scene is therefore not showing corpses but rather drowning men in their desperate struggle to survive, with the gesture of their open palms and splayed fingers signifying distress. The drowning figures have their bodies arranged obliquely with the exception of one which is drawn horizontally and which the main figure appears to be attempting to reach with his left hand.

Alternatively, it could be argued that the way the figures touch was simply a means by the artist to create "an interlocking network or web of bodies radiating out from the central ship, unifying the composition" (Hurwit 2011: 6). The fact that the heads are for the most part oriented towards the ship appears to similarly direct attention towards this focal point.

Osborne furthermore highlights the link made between the image and the oenochoe's function in the context of the symposium. This would make the vase the earliest extant example of what was to become a common equation between drunkenness and a shipwreck, with a lone symposiast as the last man standing so to speak, having not yet succumbed to the "waves of drunkenness."(Osborne 1998: 35).

Basch, L. 1978. “Le Navire mns et autre notes de voyage en Egypte,” MM 64: 99-123.

Bennett, M., A.J. Paul., and M. Iozzo. 2002. Magna Graecia: Greek Art from South Italy and Sicily. Exh. cat. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art.

Coldstream, J.N. 2003. Geometric Greece: 900-700 B.C. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Fittschen, K. 1969. Untersuchungen zum Beginn der Sagendarstellungen bei den Griechen. Berlin.

Gunter, A.C. 2014. "Contemplating an Empire: Artistic Responses to the Neo-Assyrian World," in Aruz, J. and M. Seymour (eds.) Assyria to Iberia Art and Culture in the Iron Age London: Yale University Press, 216-226.

Hall, J.M. 2002. Hellenicity. Between Ethnicity and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hurwit, J.M. 2011. “The Shipwreck of Odysseus: Strong and Weak Imagery in Late Geometric Art,” AJA 115.1: 1-18.

Kannicht, R. 1982. “Poetry and Art: Homer and the Monument Afresh,” Classical Antiquity 1.1: 70-86.

Lindenlauf, A. 2004. "The sea as a place of no return in ancient Greece," World Archaeology 35:3: 416-433.

Morrison, J.S. and R.T. Williams. 1968. Greek Oared Ships: 900-322 B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Osborne, R. 1998. Archaic and Classical Greek Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.